After days of travel by train and plane from Toronto, Asger “Red” Pedersen stepped off the plane in Kugluktuk and walked the unpaved roads of his new home. He passed tupiit (skin tents) and shack-like houses spread out across the rocky plain, at the mouth of the Coppermine River and near the coast of the Arctic Ocean. It was 1953 and Kugluktuk—still called Coppermine—was not yet a town.

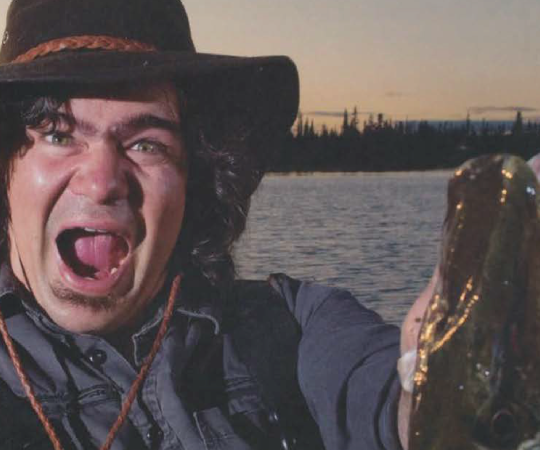

Pedersen was one of just a few foreigners and he had to adapt quickly, learning Inuktut to converse with customers in his new position as a trader with the Hudson’s Bay Company. Pedersen, 17, had been in Canada for just two years, embarking on an adventure that now took him a world away from his native Denmark.

Today, at 86 years old, Pedersen has witnessed the gradual, but drastic changes to the Nunavut community over the course of his life. The HBC trading posts are long gone. The DEW (Distant Early Warning) Line sites—built across the Arctic soon after Pederson’s arrival, during the height of the Cold War—ceased operations decades ago. Snowmachines have largely replaced the dog team; most people work in government, and not the fur trade. And the community is no longer a village of nomadic Inuit with tents and shacks spaced out across the landscape.

But Pedersen did not just sit back and watch this transformation—he played an active role in many of these changes in Kugluktuk, influencing the very shape of the community through his role as area administrator for the federal government in 1960.

In the early days, residents chose to stay in the hunting camps outside the current townsite to be closer to their traplines. But the introduction of the snowmachine made it easier for people to reach their traplines from anywhere, and residents approached Pedersen about moving the community closer together. The younger generation, in particular, was tired of being so far away from each other. “They wanted to see some other people and they wanted to go to the store [more easily],” Pedersen explains.

Although Pedersen’s job didn’t require him to get personally involved, he went out to the hunting camps and helped deconstruct the matchbox houses and rebuild them closer to the school, health centre and shops that had been set up. “So we moved a lot of the houses back into town and that was the beginning of the town structure.”

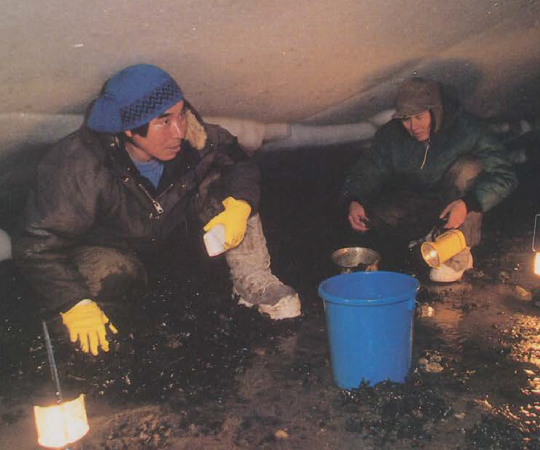

“In the short timeframe of his lifespan, the world has changed so much—especially in the North,” says Baba, one of Pedersen’s sons. “It was a very traditional nomadic lifestyle compared to today. Now, our biggest concern is if we have enough bandwidth or how slow the internet is, never mind about building an iglu or where you’re going to get your food from.”

Pedersen led his community through many of these major transitions, serving two terms as MLA (in the pre-division Northwest Territories) between 1983 and 1991. He was also a hamlet councillor and mayor in Kugluktuk, leading a local government he initially helped to establish. In his nearly 70 years in the North, he has been on almost every board in Kugluktuk and the Kitikmeot region. (Lena, his one-time wife and a political powerhouse in her own right, also served as an MLA, becoming the first woman elected to the NWT legislature in 1970. They had first met in 1959, while Pedersen was on vacation in Greenland, Lena’s home.)

It was always part of Pedersen’s plan to get into politics, he says, because he wanted to help develop the community that he calls home. During his career, Pedersen highlights his role in establishing the Kitikmeot Inuit Association (KIA) as one of his biggest achievements, along with supporting the eventual creation of Nunavut.

But Baba says his father’s greatest accomplishments may be the family’s legacy. Lena and Pedersen have six children, with a family tree that branches out to include 25 grandchildren, 47 great-grandchildren and 14 great-great-grandchildren.

“I think the biggest thing for him and for us is the family. He’s very proud to have [so many children and grandchildren],” says Baba. “We never lived in a fancy, lavish house or anything like that, but he’s always been able to help many of us family members with expenses and life regarding housing, education [and transportation]. They have been able to help us so that we could have a more comfortable lifestyle than they’ve had.”

Many of the Pedersen children—and grandchildren—became leaders themselves. When Calvin Pedersen became Kugluktuk’s MLA in 2020, he thanked his grandparents for inspiring him. “I am extremely proud to be able to call upon both of them for guidance as I believe I am the first MLA to have both grandparents serve as MLA as well,” he said in the Nunavut legislature. “I have some big shoes to fill!”

Pedersen also set an example of public service with the Canadian Rangers for decades. “I joined because my dad was a Ranger before I was born and he told me many stories about this,” says Baba, a Ranger Master Corporal, who enlisted with the Canadian Rangers in 1993. “I also joined because many of the people I looked up to as mentors were already members of the Canadian Rangers and I wanted to be just like them.” Three of Baba’s sons—and five of his grandchildren—have been or still are part of the Canadian Rangers and the junior ranger program.

It’s no wonder, after all Pedersen’s contributions to his community and to the North, that he was recently awarded the Order of Canada.

“It’s nice to be recognized for things you have done and that the society you live in seems to think it has been a worthwhile thing,” says Pedersen. “I sometimes wish they would issue these at an early stage in people’s lives so we have a longer time to perhaps enjoy it.”

The acknowledgement Pedersen is most proud of, though, is being named an honourary member of the KIA—or “honourary Inuk,” as he and Baba say. It was announced at a meeting several years ago, and Pedersen remains the only non-beneficiary to receive that title.

“Some of the work that he helped do was to ensure that NTI [Nunavut Tunngavik Inc.] and other regional associations were birthright organizations so that you can’t join unless you’ve got Inuit blood,” Baba explains. “That obviously excluded himself from ever being a member because he doesn’t have any Inuk blood himself, but all of his offspring do have that through our mother. He was very adamant on that and, even though it would exclude him, he always insists that these organizations keep it that way when they were forming their bylaws.”

The status as an honourary Inuk means the world to Pedersen. When first setting foot in Kugluktuk as a teenager, he had no idea what life held in store for him. And while he did find the adventure he was looking for, Pedersen also discovered a way of life and a community that was worth devoting himself to. And to be seen for his good heart is more than Pedersen could have asked for.

“When you’re recognized for having done something useful over a lifetime by the people that you have served, that means more because those are the people who know you.”