Everyone loves a good summer farmers' market. It’s a chance to get outside, enjoy fresh air in the company of good friends, and stock up on some of your favourite local products.

Markets in the North are no exception—but they are more than just fun, family-friendly events every week. With the high cost of retail space in the North, these markets have become vital to supporting budding entrepreneurs and providing artists with a venue to sell their work. In some communities, they are even leading the fight for a more equitable local food system, challenging people to think about where their food comes from.

Here are four farmers' markets changing their communities for the better.

Small Town Smorgasbord

Saturday is market day in Hay River. Over on Vale Island, the Fisherman’s Wharf Pavilion comes alive as people browse the wooden stalls to see what hand-made art and tasty treats the vendors have in store.

Of course, market-goers can depend on an array of locally-grown produce, with fresh herbs and greens from Riverside Growers, organic vegetables from Greenwood Gardens, and specialty items like speckled pea shoots and broccoli microgreens from Northern Greens. These stalls are usually the most popular, selling out often and quickly. “Everyone loves fresh produce,” says market manager Brenda Hall.

Then there’s the prepared foods. On this front, the market’s offerings are practically unbeatable in Hay River, with flavours from all corners of the world.

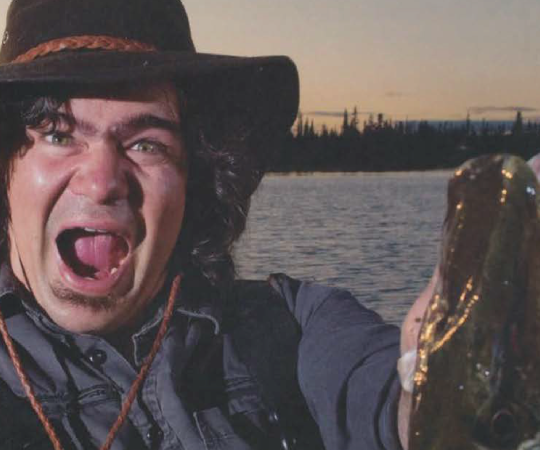

With the tantalizing smell of deep-fried whitefish wafting across the pavilion, people form a line into the parking lot for a plate of chef Shannon Buckley’s fish and chips each week. A few stalls down, the Cookin’ Cuzzins serve up bannock, soup, and the popular “taco in a bag.” Meanwhile, Masala Corner brings a taste of India to the South Slave with its chicken curry, biryani rice, and naan. Hay River resident Haidet Lacey prepares Mexican empanadas and pozole rojo, while Bonfire Bakes has vegan cookies and dessert squares for sale. And don’t forget the handmade Neapolitan-style pizza from Pizza Pig. There are just so many choices.

The Wharf presents market-goers with an opportunity to expand their palates, Hall says. And with such a diverse menu, they better be sure to bring their appetite.

The Beauty of Innovation

Whitehorse’s Fireweed Community Market prides itself on being “where local happens”—and really, it is. Over the years, it’s incubated a number of businesses now well-established within the city. Just look at Bullet Hole Bagels, which has a full-service bakery downtown, or The Kind Café with its entirely plant-based menu. Both started in a Fireweed Community Market stall.

“It’s a good space [for people to] try out recipes, and see what sells and what people like,” explains board member Katie Young. She started her own business, Klondike Kettle Corn, there in 2010.

Four years ago, the market kicked its devotion to all things local up a notch by introducing a Blue Ribbon program, which encourages vendors to purchase items from local producers and incorporate them into their products. Not only does this foster a supportive environment among businesses, Young says, but it pushes people to think outside the box. “It challenges them to be creative with what they are making.”

Many vendors have risen to that challenge. A few bakers use locally-grown berries in their sweets. Alison Pakula of Alligator’s Gourmet Grilled Cheese purchases fresh kale from a fellow vendor to make a side salad for her sandwiches. Even Young got in on the action. She uses fresh dill and chives from market farmers to create her dill pickle popcorn flavour, and it’s since become a Klondike Kettle Corn staple.

“People are really proud to use local ingredients, and they’re happy to share that with their customers,” Young says. “I think customers see value in that, too.”

The Arts Come Alive

Few places in the North boast a livelier arts scene than Dawson City, and one of its most enduring traditions is the weekly summer Artist Market hosted by the Klondike Institute of Art & Culture (KIAC). Every Saturday, painters, carvers, ceramicists and artists of all disciplines set up shop in Waterfront Park’s wooden gazebo, eager to share and sell their work. That is, until the pandemic struck in 2020, and the market was temporarily put on ice.

Luckily, the Dawson Farmers' Market was quick to come to the rescue. It offered up space at its weekly outdoor market (which had been allowed to continue) and welcomed those artists to join.

For board member Sherry Masters, the decision was a no-brainer: “Artists and farmers have to have a place [to sell].” It also creates a more dynamic and interesting market for people to visit every week—a place where small-scale, local food producers and artists are given the chance to shine.

“You need your artists and you need your trinket sellers,” Masters says. “They’re what keep the market alive.”

Though KIAC has since resumed its Artist Market, some vendors have opted to stay outside too. One constant presence at the farmers market is carver Wanda Jackel, who works primarily with bone and antler. “She’s prolific, and her work is incredible,” Masters says.

Seeding Change

The Yellowknife Farmers Market takes its commitment to the community very seriously. In fact, it has a steadfast mission to be the city’s premier space for education on the importance of local food production.

“Food is not a simple issue,” says France Benoit, a founding member of the market and owner of the urban farm Le Refuge. “It’s a web of issues, and we’re trying to address all of them within the confines of an organization such as a farmers market.”

Since it began in 2013, the market has continually grown its roster of educational programs meant to engage the community. For example, it hosts the popular “Lunch and Learn” series in the summer at the public library, with lessons and helpful advice on how to grow vegetables. The “Eat Local YK” table offers recipes and tips on using locally-grown items every week, while backyard gardeners can bring their excess produce to the Harvesters Table and sell it.

There’s also a waste reduction and composting initiative, financial aid for lower-income families, and a land-share program that connects landowners with growers.

Yet its most ambitious project to date has been developing the Yellowknife Food Charter. Released in 2016, the document called for a local food system that was accessible, sustainable, and fair for everyone, and outlined the group’s intentions to lead by example.

Now, the market board is assisting the City of Yellowknife to implement its food and agriculture strategy, which was inspired to a great degree by the charter. The strategy promises to support urban agriculture and grow the local food economy.

“Ultimately, it’s about feeding ourselves as a community,” Benoit says. “We (the Yellowknife Farmers' Market) want to play a big part in that.”

What about Nunavut?

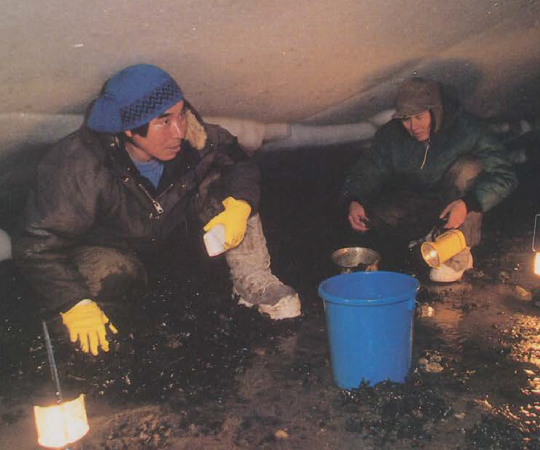

The idea of getting together and sharing food with the community is central to life in Nunavut. It’s an Inuit custom for hunters to share their harvest with families, elders and others in need.

But unlike its territorial neighbours, there aren’t any consistent farmers markets in Nunavut–likely because there is less established agricultural infrastructure. (Although it’s not uncommon to see the odd greenhouse here or there.)

The closest thing to a farmers' market is the Piruqtuviniit Food Box program run by the Qajuqturvik Community Food Centre in Iqaluit, which gives residents the ability to buy a box of fresh produce and eggs every week. The food is purchased wholesale, meaning it’s often cheaper and fresher than what can be found in local grocery stores. Organic and Canadian-grown items are given priority. It’s a pay-what-you-can system too, so people can get one no matter their income level. Boxes go for anywhere from $5 to $70, with about 70 distributed each week.

“It provides a really great opportunity for us to engage with our community members and have conversations about nutrition, the different recipes they can try, and the methods of cooking foods they might not be familiar with,” says Rachel Blais, the centre’s executive director. Items included vary from week to week. Customers might receive strawberries and swiss chard one week; the next, they’ll get oyster mushrooms and avocados.

Sales also serve as a source of income for the centre, which offers daily community meals, cooking classes, and a free country food box distributed monthly to local elders. The end goal, according to Blais, is creating a more equitable food system in the city.

“Everyone should have access to affordable, fresh and nutritious food, regardless of their financial situation,” Blais says. “And [the food box] is a great example of a community approach to addressing food insecurity.”