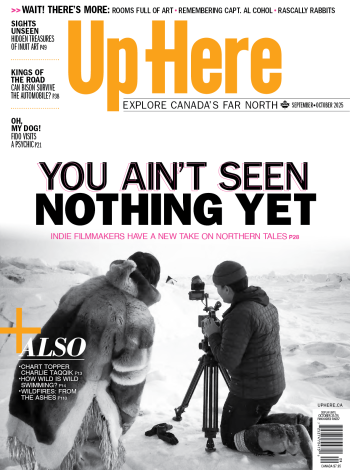

Jay Bulckaert fell in love with film as a kid. “That was always the plan,” says the co-creator of Yellowknife’s Artless Collective. And for a while, it was. Bulckaert and production partner Pablo Saravanja launched the Dead North Film Festival in 2012. Over the past seven years the scrappy sci-fi, fantasy, and horror genre festival has screened over 400 made-in-the-North short films.

But now television is Dead North’s future. Bulckaert and Saravanja are busy developing their most ambitious project to date: an anthology show of horror and fantasy stories featuring a rotating roster of northern filmmakers behind the lens. Picture The Twilight Zone, but set in the territories. If everything goes according to plan, Dead North the TV series will be streaming online and on television within a couple of years. The challenge will be, well, everything.

“The weather is going to suck. Finding money is going to be really hard,” says Bulckaert. “We’re up against way more than anyone else.”

That’s a collective ‘we.’ What the three territories have in common, says the duo, is regional isolation. The cost of producing television is as extraordinarily expensive as anything else in the territories, but with fewer funding options for creative minds. Nevertheless, community-created television in the North isn’t a new concept.

Call it public access, call it community TV. It’s often low budget, unpolished, and operating on a different aesthetic wavelength than primetime network programming. It’s exactly what makes community TV in the North so special. The medium is the message: a place for northern voices to tell northern stories on channels long dominated by southern stories.

“The vast majority of the media we see happens in major cities, the opinions of those shows, the narrative of those shows is written by a southern perspective,” says Bulckaert.

A lifetime ago there was no northern-made television. Broadcast tapes of CBC programs would be flown up into remote communities. They brought with them hockey scores, government news, and a monoculture of language and story. The clichés of network TV spread easily throughout the Arctic. Broadcast through the airwaves was an entire world of English-speaking white men heroically framed by television’s technicolour spotlight, all created and captured in a Toronto studio.

Fearing the idiot box would cause irreparable harm to their lifestyle, the elders of Igloolik banned the device in 1969 for several years. They weren’t Luddites. They simply saw the true cost of southern television; they saw what was important. Northern stories needed to be told by Northerners. It’s no coincidence that Igloolik is the home of Isuma Productions. Zacharias Kunuk co-founded Canada’s first independent Inuit film and TV production company in 1990 to help tell Indigenous stories.

The Inuit Tapiriit of Canada (forerunner to Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami) had a similar plan when it launched the Inukshuk Project in 1980, linking six communities (Iqaluit, Pond Inlet, Igloolik, Baker Lake, Arviat, and Cambridge Bay) by satellite and allowing the transmission of television signals from a studio in Iqaluit. The Inuit Broadcasting Corporation was licensed by the CRTC a year later and began producing Inuktitut-language television. Those early days featured live coverage of the 1983 Inuit Circumpolar Conference, current affairs magazine Qaqqiq, and North America’s first and longest-running Indigenous language program for children, Takuginai. CBC North also began to expand its TV content in the ’80s, moving the broadcaster’s first Inuktitut program, Taqravut, up from Montreal to Iqaluit in 1987. In 1993, Television Northern Canada—the North’s first entirely circumpolar TV channel—launched. A few years later it would evolve into the Aboriginal People’s Television Network, which celebrated its 20th anniversary this past September. From IBC and APTN to Northwestel (and smaller cable channels like Rolf Hougen’s WHTV in the Yukon), Northerners carved out a place for themselves in the television landscape.

“I think it’s really important for Northerners to have a place on the world stage to communicate their voice,” says Bulckaert. “The way someone from New York would come up to Sachs Harbour and represent Sachs Harbour is not how Sachs Harbour is in real life.”

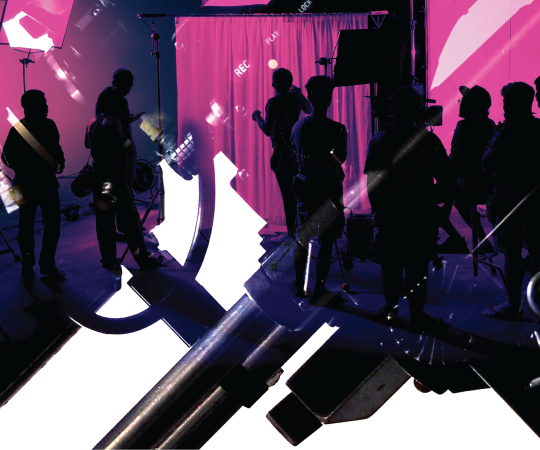

Dead North is designed, in part, to find and showcase that northern perspective. Each episode of the anthology series will feature a different writer and director, pulling from a curated shortlist of territorial filmmakers, emphasizing Indigenous and female voices. The creative minds who, as Saravanja puts it, are right now “busting balls in the coldest, darkest part of the year for no money.”

As he alludes, there’s also an economic incentive. Television, potentially has a much bigger financial bang for its buck than working on a feature film. The latter offers a few weeks of employment every couple of years. With a plan for six one-hour episodes, Dead North could offer four months of well-paid work each year over multiple seasons for its northern crew members. “I’m born and raised in the Northwest Territories,” says Saravanja. “I’m a lifer. I want to be here.

I’ve invested my life savings into living here. I’ve invested my entire career into living here and working here. It’s important to me as someone who grew up here to create opportunities for the next voices.”

Creating those opportunities is part of Shawn Jo’s job. As Northwestel’s community TV production technician, he’s responsible for shooting and editing all the locally-sourced television shows the cable company broadcasts. Included in that schedule are in-house productions and ideas pitched from creative teams across the Yukon and NWT. Storytellers get funding, technical help, and a commitment to air the show. “All the projects that go around in northern Canada, especially the ones that come to our attention, we try our best to give them guidance and make sure these things happen,” he says. “Having community TV that can hold your hand a little bit and guide you through it, just having your back basically, is tremendously helpful.”

Northwestel’s community productions include information programs like The Boreal Herbal, competition shows like Garage Sale Scavenger Hunt, and documentaries such as Dakhká Khwáan Remix, which follows the Yukon’s Tlingit Dakhká Khwáan Dancers as they create and record a double album of traditional and modern songs. It’s reality television; emphasis on the real.

“Being community TV, we don’t have to follow the pre-established rules,” says Jo. “All we want to do is create and celebrate local content... However that means, we’ll try our best to achieve it.”

Take the Dakhká Khwáan Dancers, for example. The series spent time in the recording studio, documented the history of the Tlingit Nation, and followed the dancers to the troupe’s 10th-anniversary performance. A southern production wouldn’t have spent the time to allow for that kind of in-depth coverage. Even with smaller budgets and bigger production constraints, northern television is a richer product for its viewers.

“Creating local programs, they’re of the perspective of locals,” says Jo. “They’re given depth.”

“When you’re surrounded by cultural and artistic influence and millions of people, your stories become homogenous,” adds Saravanja. “What we have going against us [in the North] sometimes is also what goes for us.”

Back at Artless’ production office in Yel- lowknife’s Old Town, Bulckaert and Saravanja are gearing up to apply for the National Screen Institute’s TV incubator program. If they make it in, Dead North will be fast-tracked and production will ramp up quickly.

“I‘ve got to stop saying ‘if’ we pull this off, and say ‘when’ we pull this off because it feels like a crazy mountain to climb,” says Bulckaert. “Sometimes, I can’t believe we’re at this stage and talking about this realistically. But it is real, and once we pull this off, this will change the industry in our town, and probably in the Yukon, more than anything else that’s ever been done.”

The first two scripts are already complete. One, based on a short Bulckaert created for the Dead North film festival, is a sci-fi horror story about the aurora. The second, written by Outpost 31 (Artless’ production partners in the Yukon) is a Lovecraft-inspired teleplay cheekily called “Make Cthulhu Great Again.”

The dream is to land the show a home on a big-market streaming site like Netflix or Crave. But Bulckaert and Saravanja both are adamant they’ll sacrifice take-home money for artistic freedom. Northern creativity is what matters most. For their show, and for so many others produced across the Arctic.

Still, even if the stars align and everything goes according to plan (and nothing ever goes according to plan) it could take another two years before audiences will be able to tune in to Dead North. But that’s OK, Bulckaert says. There’s no need to rush.

“This is our show. As in, this is the North’s show,” he says. “If it takes us three years to develop something... that’s OK. We want to do it right.”