The ‘70s were a decade of dramatic social and political change in the North. In 1973, Yukon First Nations initiated what would be the first set of negotiations toward self-government. In 1974, Justice Thomas Berger set out on the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry, holding hearings across the North on a proposed project to pipe gas to the south. In 1976, Inuit Tapirisat of Canada launched negotiations for what would lead to the creation of Nunavut. Amid all that movement, communities were gradually growing, gaining new infrastructure, and witnessing an influx of southerners. What did it all look like on the ground? We peeked into a few photo albums to find out.

1. Worldly possessions (lead photo)

In 1976, Dorothy Eber, one of the first Canadian authors to record the oral history of the Inuit, asked photographer Tessa Macintosh for a portrait of a Cape Dorset artist named Anirnik. Anirnik didn’t really have a family name—most Inuit were just acquiring them at the time.

“I was struck by what she put on the wall,” says Macintosh. “People were paying big money for her drawings. She would go to the store and buy this”—arrays of plastic ribbons—“and it worked for her.”

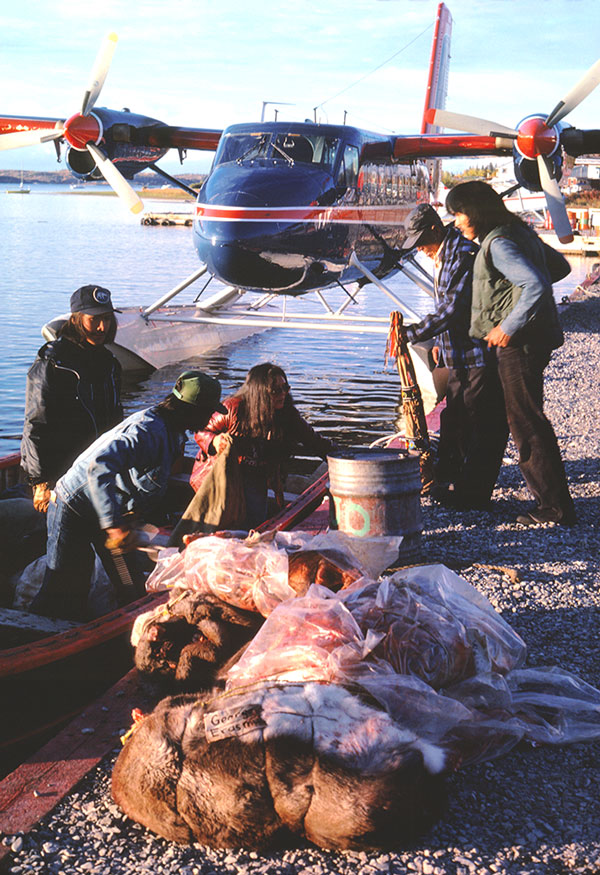

2. The name-changers

When Tessa Macintosh heard that her friends George Potfighter, his sister Alizette, and friends were back from their fall hunt, she headed to the Yellowknife dock to capture the unloading.

Alizette was a founding member of the NWT Native Women’s Association. It held its first conference earlier that year, in July 1977, and continues to lobby on behalf of aboriginal women in the NWT today.

The Potfighters have since changed their names: George now goes by the family name Tatsiechele; Alizette uses her married last name, Lockhart.

And if you look really closely, Georges Erasmus has his name on one of the caribou bundles—presumably, it’s meant for him. At the time, he was president of what was then known as the Indian Brotherhood of the Northwest Territories. In 1978, the Indian Brotherhood voted to formally change its name to the Dene Nation, which had mobilized to protest the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline and negotiate their land claims with a unified voice.

3. Who needs pants?

Tim Schowalter didn’t want to dive into the freezing-cold water. He’d just rappelled halfway down a cliff to examine a peregrine falcon nest perched along the cliff as part of a survey of Yukon raptors. Since the rope he was using was brand new and too smooth to climb back up, his only way out was to dive into the river below. “I thought I needed a bath by then anyway,” he jokes.

Now retired and living in Alberta, the wildlife biologist spent the summer of 1973 in Old Crow, Yukon, studying the potential effects the proposed Mackenzie Valley Pipeline might have on birds of prey. The study, commissioned by the Canadian Wildlife Service, found that the pipeline would be harmful to peregrine falcons indirectly: it would have to be constructed on a ridge, which would be made of gravel collected from blasting nearby cliffs where falcons nest.

Soon after that study, says Schowalter, the peregrine falcon disappeared from the area. The study had also found pesticides in the birds’ eggs, probably picked up when the falcons migrated south every year.

Four years later, the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry would recommend that the pipeline not be built through the northern Yukon at all. Schowalter doesn’t think his study played a significant role in that decision. “But it was part of the bigger picture.”

4. Ice jam traffic

The flooding started sometime in the night. Schowalter woke up to a pilot pounding on the door of his trailer. An ice jam on the Porcupine had flooded Old Crow, as it does most years after spring breakup, and large chunks of ice were floating through town. Luckily, nobody was hurt.

While out surveying the damage, Schowalter spotted Stephen Frost and his daughter Louise paddling through the streets in their canvas rat canoe, which they’d normally use to go trapping for muskrat.

Stephen, now 82 and still living in Old Crow, was a renowned musher during the ’60s. Louise became an avid cross-country skier. She now lives in Prince George, B.C.

Stephen doesn’t remember that particular flood. The one that stands out in his memory, which he admits is failing, was in the early ’90s—a few years before Old Crow, home of the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation, secured self-government.

Every spring since, the Porcupine River’s waters have risen, threatening another big flood. So far, it hasn’t come.

5. First look

Ellen Ittunga, Michael Tucktoo and Johnny Kootook watch the fall sealift being unloaded in Taloyoak (then called Spence Bay) in 1976. Actually, says Nick Newbery, Ittunga is watching the sealift; “the boys were watching her.”

When the sealift arrived every September, “the town sort of stopped,” recalls Newbery, who taught school in what is now Nunavut from 1976 to 2005. “All the boys would disappear for two or three days, because they’d be hired as stevedores and carry all the stuff to the Hudson’s Bay Company.”

Newbery never taught Ittunga, but he became a close friend of her family’s—“I was in their house a lot and had Christmas with them.” Coincidentally, Ittunga, who was in kindergarten when the photo was taken, ended up following in his footsteps. She recently got her Bachelor in Education in Iqaluit and is back in Taloyoak, teaching Grade 2. Today, she says, it's still cheaper to have bulk items shipped up via sealift than to shop locally.

6. Breaking ground

In the 1970s, the government made a push to build permanent runways for several small Arctic communities, including Taloyoak.

“All we had till then was a bumpy sand strip, with two crashed aircraft lying beside it, for summer use, and an ice strip cleared by our Cat on the bay below town for winter use,” says Newbery. “Night lighting consisted of metal balls filled with gas with wicks, mounted on two rows of 45-gallon oil drums.”

Work began in 1977. In March—when this photo was taken—a military Buffalo aircraft brought in the advance party to scout out the location for the new runway. They let everyone in town check out the aircraft, proving to be “good public relations.”

The military would send another aircraft, a Hercules, in the early summer to drop off more crew and equipment. Construction would go on all season long until the snow came back. Three summers later, and two decades after people moved off the land and into town, Taloyoak had its permanent runway.

7. Fools rush in

During the gas can balancing race, a beloved tradition of the spring games, contestants had to tow empty five-gallon gas cans on caribou skins. If the gas can rolled off, they had to stop and put it back.

“It looks dead easy, but it’s very hard,” says Newbery. “Any little bump, and it goes flying.” Usually, it was the more seasoned, patient snowmobilers who managed to keep the gas can in place. “The young and eager invariably lost theirs.”

Taloyoak took turns with nearby Kugaaruk (then Pelly Bay) and Gjoa Haven hosting the weekend-long spring games.

Nowadays, “it’s not that different,” says Newbery. “People still play those games today.”