Ah, summer... But if you’re past puberty, chances are you’re working through at least part of it. Not all summer jobs are created equal—oh no. We’re not talking about the indignity of wearing a polyester uniform and smelling of burger grease until September. We’re talking about Northern jobs that put lives at risk, mental states in question and leave you scratching any exposed skin. There are tough summer jobs, and then there are these seasonal sentences. So what is it that keeps people coming back?

Alone at the top of the world

Managing with wolves in Quttinirpaaq National Park

One may be the loneliest number, but spread even a handful of people over a national park covering 37,775 square kilometres and it can feel like you’re alone on the moon.

Sign Jenn Lukacic up. She’s the acting park manager for Quttinirpaaq National Park (“top of the world” in Inuktitut), the most northerly park in the country, located on the tip of Ellesmere Island in Nunavut. Because of its location, it’s a part of the country few people have seen. Last year, the park had 21 visitors, which was an actual increase from the year before when only 17 people made the trip. (This July, it will be positively swarming with visitors, when 16 people will head in at once.)

In Quttinirpaaq, there are more wolves than people. “Probably one of my most memorable and favourite times was very early in the season at Lake Hazen. A wolf just happened to be on the other side of the bay, a few hundred metres away probably, and he graced us with some lovely howling,” says Lukacic. “He just wanted to say ‘hi.’ It was a very serene kind of experience.”

She was definitely on the wolf’s turf, but she wasn’t scared. “We’re prepared for that. We’re trained for that,” says Lukacic. “The wildlife, they don’t see a lot of people and so they naturally are curious, but not to a degree where we would feel unsafe.”

Park employees work in teams of two to four, some cycling out while others spend the entire field season from mid-May until the middle of August in the park. They do have access to the rest of the world via satellite phone, but getting items in or out of the park is a pain. “I would say that’s probably our biggest challenge,” says Lukacic.

Once there, they spend much of their time patrolling, exploring visitor routes and hiking trail opportunities. “We may check on some archeological sites,” she says. “And when we’re on those patrols we’re essentially backpacking. We carry tents and our food and our stove and our communication equipment.

It’s very interesting to come back to, you know, internet and roads and just city noise.

“It’s the best part of the job. Being on the land, it’s an absolutely amazing place to see and experience. It’s really quiet, it’s very peaceful, very dynamic. The landscape is just infinitely fascinating,” she says. They occasionally bump into researchers or park visitors while out there.

Though the idea of even an overnight business trip with coworkers may cause some to recoil in horror, Lukacic and her team sign up to live and work in close quarters with each other for months at a time. On purpose. “You get to meet a bunch of really great and passionate people who love the park and the work that they do as well.”

When she does return to metropolitan centres like Iqaluit, it can be a shock to the system. “It’s a bit of a transition for sure. It’s very interesting to come back to, you know, internet and roads and just city noise. That’s actually something that I really quite enjoy about it—it’s not having those distractions of day-to-day life.”

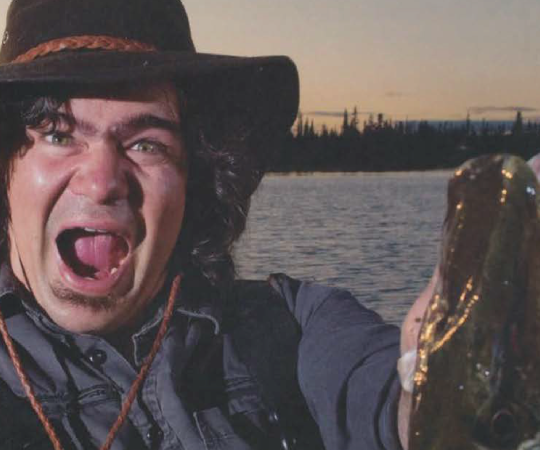

Trying to get a bite

Mosquito researcher in the Torngat Mountains

There are two seasons in the North—winter and mosquito. For most people, that means snuggling up close with as much DEET as they can tolerate. But not Fiona Hunter. She’s a professor of medical and veterinary entomology at Brock University and summertime is hunting season. In 2012, she gathered her nets and traps and jumped into a chopper in the Torngat Mountains in Nunatsiavut to capture mosquitoes, blackflies and other biting insects. She was there to find out what makes them tick. She and her fellow researchers were the bait.

“We trap them using collection from self,” she says. This is a technical way of saying she takes them live when they land on her and try to bite. They use a few other methods too, like netting in vegetation, light traps and ‘malaise traps’—tents with an opening at the bottom, where the insects enter, topped with a cylinder filled with poison.

But people are still the prime lure. “I never use insect repellent when I am working because I don’t want to contaminate my equipment,” she says. (Hunter will spray on bug dope when she’s outdoors on her own. She’s not crazy.) “In the Torngats, the mosquitoes were so thick that we used bug jackets with screening over our faces and torsos to avoid being harassed.”

Does that mean she gets bit herself? Yes. A lot. But she loves it.

“I think I’m just an entomological nerd,” she says. “And I especially love biting-flies. I have spent my entire academic career studying biting-flies.” Her favourite biting-fly—yes, she has a favourite—is the black fly because it’s so robust that you don’t have to worry about breaking off its legs or rubbing off its scales when you handle it. But the black fly is less valuable, from a research perspective, than another Northern staple. “Mosquitoes are obviously of more importance in Canada in terms of disease transmission.”

Her latest research focuses on the Zika virus in the Dominican Republic. But no matter where she is, one thing is true: mosquitoes thrive in some of the world’s most incredible landscapes. Her Nunatsiavut research was located io Saglek Fiord and Nachvak Fiord, in the Ivitak Valley, which could only be reached by helicopter. “It was one of the most spectacular places I have been—and also one of the most unique. Our campsite was surrounded by electric fence wire due to the threat of bears. It was truly humbling,” she says.

Hunter was in the Torngats to determine whether there were actually more mosquitoes than in past years and, if so, why? People in the region had noticed an increase. Were these ‘mosquito tourists,’ interlopers that had moved into the area from elsewhere? Or was something else to blame?

It turns out the vast majority of the mosquitoes that attacked her were Aedes hexodontus, which have high numbers in the northern fringes of the boreal forest and adjacent tundra in Canada, Alaska and Eurasia. Their larvae don’t do well at lower temperatures, but

as the North warms, they are better able to survive the winter and hatch in spring in larger numbers. She wrote to a colleague that perhaps things were warming up in the Torngats to allow that species to thrive. “My feeling was that Aedes was doing better than previously in the Torngats, but without historical identification data, there was no way to tell whether it had been there all along.”

Which is why, besides the chance to commune with biting-flies, one of the things that she most valued from the trip was the time spent with locals. “When we were in the Torngats, we met with elders from the community and heard what they could recall about mosquitoes,” she says. “I explained the lifecycle of mosquitoes and showed them how there are many different species of mosquito and how one can tell them apart with photographs that had been taken down a microscope.”

“It was a very rich exchange,” she says. “They taught me a lot.”

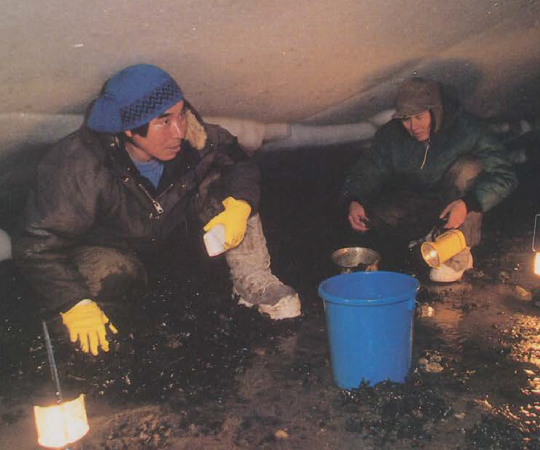

Scorched earth responsibilities

Fighting fires in remote Northern forests

Sometimes finding a water source to fight a blaze is as easy dropping a pump into a lake. But it can also mean digging up a swamp in intense summer heat while swarms of bugs threaten to lift you up by your heavy protective gear. Ian Ziemann did just that in 2016 when he and his crew were out in Carson’s Landing in Wood Buffalo National Park battling a massive blaze.

It’s hot. It’s dry. And it’s the dirty job to end all dirty jobs. With dozens of fires raging across remote regions of the North during the hottest months of the year, crews like Ziemann’s walk towards fires that any seemingly sane person would speed away from. But the excitement is precisely why he loves it.

He estimates he was dispatched to about 15 fires last summer. His team assesses wildfires and if they’re a threat to the public, to towns, cabins, infrastructure, mines or culturally important areas, they’ll head out to fight them. “What we try to do is contain the perimeter of the fire, and then once we’re confident enough that the fire’s not going to go anywhere, we start doing the mop up,” he says. “That’s when we start going further in and taking care of all the little hot spots and stuff that there might be.”

Ziemann is a renewable resource officer with the GNWT these days, but he’s hoping to get out to a few fires this summer. He comes by it naturally: his mom fought fires. “When I talk to her about it, it’s like we have something to share and I can gain knowledge from her all the time,” he says.

Wearing flame-resistant clothing, hard hats and boots, teams of firefighters head into the wilderness with pumps, hose packs and shovels, plus food and water. Because many fires are in remote locations, he can be out battling a blaze for a day, or a couple of weeks, working 12-hour days. Last summer, he travelled to British Columbia for the job and camped in a tent at the Williams Lake airport for 21 days. “That thick smoke in B.C. was pretty crazy,” he says.

They’re at the mercy of whatever water they encounter, so they come equipped with pumps that can tap into any nearby lake or river, and helicopters that send buckets of water down on the flames.

Wildfires can heat the air up to 800C. Ziemann says it shouldn’t get that hot around them—if it does, it means they are moving too fast. “We take breaks, especially if it’s really, really hot out, like 34 or 35 degrees Celsius. I try to encourage the guys to take more breaks, even like five minutes, to cool down a little bit, drink some water.”

He can’t remember being afraid when facing a fire. “You’re with a group of people, everyone has the same objective. We’re a team so, you know, the fear kind of goes out the window, I think.”

That camaraderie is the best part for him. “You work with your friends and I think everyone has a pretty good time,” he says. One of his proudest moments was arriving at a fire in Wood Buffalo National Park with another crew heading one way around the fire while his team headed the other. In less than four hours they met up, and got the flames under control.

“We’re essentially protecting the public from these forest fires, because some of them can get pretty out of control. At the end of the day safety is a big thing too. We want all of our workers to go home, and I want to go home too.”