The bad news came on a Thursday morning. It was April 30, and an individual in Nunavut had just received a positive result from a test for COVID-19. The territory’s first confirmed case of the virus that had been sweeping the planet was in Pond Inlet, the scenery-rich hamlet at the northeastern corner of Baffin Island.

“There is no need to panic,” Premier Joe Savikataaq said in a news release sent out that morning. “Nunavut has had time to prepare, and we are in a solid position to manage this. We ask people not to place any blame, not to shame and to support communities and each other as we overcome COVID-19 in Nunavut.”

The case was worrisome—and puzzling. Five weeks had passed since the territory entered a state of near-total isolation, sealing itself off from the rest of locked-down North America. The government had barred most non-residents from traveling there and required residents who’d gone outside Nunavut to spend 14 days in self-isolation centres set up in southern cities before returning home. Public gatherings had been banned, and residents had been urged to stay home as much as possible and practice physical distancing. Everyone knew that Nunavut, with limited medical infrastructure spread out across a few dozen fly-in communities, was especially vulnerable. The virus had already arrived in the Yukon and the Northwest Territories, with a handful of cases each, while in northern Quebec, Nunavik was attempting to contain several clusters. Nunavut was the last jurisdiction in Canada without any confirmed cases. In some ways, COVID’s arrival felt grimly inevitable. Still, how had the virus slipped through the barriers put up to block its transit from south to north? And how far had it already spread?

As a public health rapid-response team flew from Iqaluit to Pond through a Baffin Island blizzard, landing in whiteout conditions, and as contact tracers swung into action, the 1,600-odd citizens of the hamlet were left to wait and worry. Joshua Arreak, Pond Inlet’s mayor, says the test result “caught us off guard.

“It felt like we failed or something, for the whole of Nunavut.”

Pond’s two stores, the Northern and the Co-op, were both abruptly closed to the public. Residents were told to stay home, and all regular scheduled passenger flights in and out of the hamlet were canceled for the next two weeks. Suddenly, Pond Inlet was cut off from the world, and every household within Pond Inlet was cut off from one another, too. There was nowhere to buy groceries, no place to gather and share news, no way in or out.

“I got really shocked and scared,” says Fiona Aglak, a resident who works as a host at Pond Inlet’s community radio station. But despite her fear, she kept going to work. The station, remaining open while everything else closed, would play a key role in how Pond’s residents weathered the next few days. The airwaves became the thread that tied everyone together.

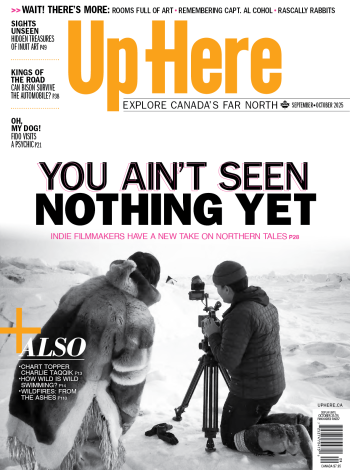

Connected to the rest of Canada only by tenuous flight schedules and a couple of two-lane highways, the North is both uniquely vulnerable to a disease like COVID-19, and uniquely suited to weather it. “This could either be the best place in the world to be or it could be the worst place in the world to be,” says Pat Kane, a Yellowknife-based photographer. (Kane is a former photo editor at Up Here.) From the start of the pandemic in Canada, he says, “I think everybody realized that. Everybody was like, we cannot let this get out, or let it spread in the North.” That sentiment seemed to be shared by governments and residents throughout the territories. Like Nunavut, the Northwest Territories locked down its borders in mid-March, and the Yukon followed suit soon after (with exemptions for travelers using its thin road network to get to Alaska or to the Mackenzie Delta region of the NWT).

The spectre of a vicious, communicable virus getting loose in communities without any doctors, let alone ICU beds, was terrifying. Medevac flights, dependent on decent flying weather, could only connect to southern hospitals if those hospitals weren’t yet overrun. Meanwhile, in too many northern communities, housing is overcrowded and the idea of isolating COVID patients as recommended, in their own space with their own bathroom, is impossible. Elders, especially vulnerable to the virus, are crucial keepers of knowledge about languages and cultures already threatened by colonization. The North's best hope, it seemed, was to use geography to our advantage.

But some outsiders saw the advantage, too. An early scare in the Yukon drove home the region’s vulnerability. In late March, as the pandemic accelerated in southern cities, a couple from Quebec decided that the Arctic would offer them a safe escape from the virus. They drove west and north to Whitehorse (the Yukon had yet to close its borders to non-essential travel at that point), where they managed, despite safeguards, to get on a plane to Old Crow. They were, apparently, intending to live off the land in the territory’s only fly-in community—though they lacked any plans or knowledge on how to do so. “It’s not like you wake up in the morning and birds dress you,” Dana Tizya-Tramm, chief of the Old Crow-based Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation, told VICE News at the time. The couple was intercepted at the Old Crow airport, isolated in one of the Co-op’s hotel rooms, and bundled onto the next plane to Whitehorse.

Yukoners were furious and frightened. The incident went viral, but happily the couple’s recklessness didn’t result in transmission of the virus. The Yukon tightened its restrictions soon after, and there were no further attempts, that we know of, by southern Canadians to use the North as their personal escape hatch. Instead, the territories settled into a new routine of physical distancing and household isolation.

It might seem as though Northerners would be accustomed to that sort of thing. But, says Kane, “this is actually quite unusual, I think, for Northerners to be inside and away from each other. We’re so social and we’re so interactive with each other, that this is exceptionally strange to us.”

The lockdown was still fresh when Kane decided to try to capture that strangeness with his camera. He was sitting at home one night with his wife when she suggested, jokingly, that taking family portraits through people’s windows would be a hilarious way to pass the time. Kane posted the idea, still joking, to Facebook. But people responded immediately to say they’d be game. “I thought about it overnight after getting all these requests, and I was like, this would actually be a really cool way to document this time.”

With a number of work assignments canceled by the pandemic, he had the hours to spare. Kane set out to shoot what he called his isolation portraits, and the early, joking nature of the project quickly fell away. The resulting photos are moody and bittersweet. They show Yellowknife residents, behind glass, squinting into the low winter sun. The world outside is reflected in the panes—close but far away. In one, a small child presses its hands flat against the glass; in another, girls in pointy party hats lean out an open window—a birthday party of two.

“It was energizing to do, it got me outside, it got me to interact with people that I either hadn’t seen in a long time or have never met before. It was a creative process that everyone was into, and it gave people a little souvenir of the time,” says Kane. “But it was also very sad. We’re not used to being locked up behind windows.

“I think people in the south, and people who’ve never been to the North, might view us as people who are in the cold all the time and live in the dark; people who live in the bush, are isolated from everybody. Whereas in reality we’re very social, we’re very engaged with our communities.”

The pandemic left Northerners with a critical question: How do you support each other and stand together when you have to remain apart?

In Pond Inlet, the community weathered the hard days immediately following the positive test result, in part, thanks to the power of radio.

Fiona Aglak was on duty at the radio station in the days after the positive test. She and others extended their usual working hours and stayed on the air. Initially, the focus was on relaying the latest instructions and developments on Pond’s lockdown to everyone stuck at home. “We needed to hear the news,” she says. But soon the station broadened its mission to keeping up people’s spirits, keeping everyone engaged and entertained. The station started hosting games, with cash prizes— some donated by the hamlet government, others fundraised from listeners—and encouraging residents to call in and tell stories.

“Funny things that happened in your life, or the most memorable moment in your life when you were out camping, that kind of thing,” says David Qamaniq, the territorial MLA for the area. “People were working together to try to entertain themselves.”

“It was actually pretty fun after a day or two,” says Aglak. She thinks the programming helped people—it certainly helped her. One game, she recalls, raised more than $400 in prize money. She figures that listenership was much higher than usual, as well.

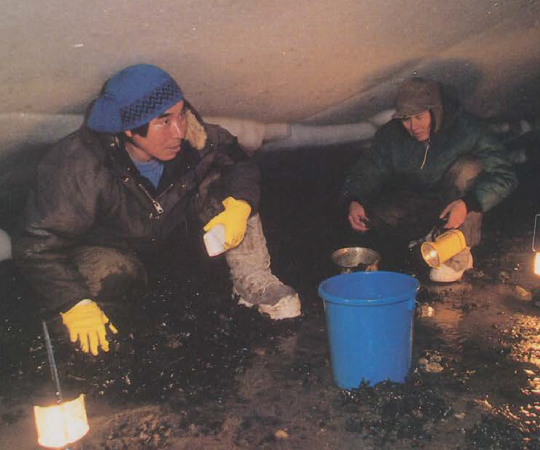

After that first tense day, following guidance from the government’s response team, the stores reopened, allowing a maximum of 10 masked, physically-distanced customers inside at a time. That came as a relief to residents who’d had no warning or time to buy essentials. Access to food can be fraught in the North’s remote communities at the best of times, and the closures had been a source of anxiety for many. (Throughout the lockdown, the children’s breakfast program that would normally be accessed through Pond Inlet’s school shifted to home delivery. Elders have also received food, and the local Hunters and Trappers Organization has distributed fish and seal.)

Mayor Arreak says that Inuit history has helped to prepare the community for hardship. “Throughout history, there’s been some death and accidents and people being lost in families, so we have experienced that,” he says.

Two examples of past plagues still scar the North. The 1918 flu decimated populations—one Inupiat community in Alaska is estimated to have lost half of its members to that pandemic—and Nunavut continues to battle against tuberculosis.

“I think Inuit are always prepared for things like that,” says Arreak. “It’s not the end of the world, and if it happens to us then it will happen to us, but let’s be prepared and support each other. And there was a lot of support going around.”

That was the story elsewhere in the North, too: communities coming together to support each other while staying apart. Tuktoyaktuk, a hamlet of 900 or so residents in the Mackenzie Delta, launched the largest community hunt in its history in late March. The aim was to take pressure off the tenuous supply lines that snake from southern centres up the Dempster Highway to the Arctic Coast, and to ensure elders and others had an adequate supply of game. “COVID-19 has no end date,” Tuk’s mayor, Erwin Elias, told the Inuvik Drum.

Just south of Tuk, residents of Fort McPherson soon realized that truckers bringing essential supplies up the Dempster were sometimes being stranded in the area by highway closures. With no restaurant in the community, and limited store hours, that meant the truck drivers were sometimes caught without any food. The residents organized and stepped in to make sure the drivers were caffeinated and fed.

In Whitehorse, Yukon Brewing, which also makes spirits, turned its distillery operation to the production of hand sanitizer for local front-line workers, to combat early shortages. The sanitizer was distributed through the RCMP, at first, but when the brewery had sufficient supply, they staged a drive-through fundraiser for the food bank. Volunteers used long-handled fishing nets to collect cash from drivers, who then claimed 500-ml bottles of hand sanitizer in exchange. The giveaway raised more than $8,500.

Across the North, crafters sewed homemade masks. In Old Crow, the RCMP detachment got involved in delivering groceries to elders. Companies donated laptops so kids could home-school.

Still, the stresses of the pandemic continue to be significant, especially in communities whose resources are often strained to begin with. As the lockdown wore on, the Yukon’s chief medical officer of health, Dr. Brendan Hanley, expressed concern about the secondary threats of COVID-19: loneliness; depression; anxiety; economic hardship; and the pain and danger that comes when people are reluctant or unable to seek out medical care for other ailments. The Yukon has seen an apparent spike in overdose deaths since the pandemic began. People are coming together, but the list of problems to be tackled is long, and growing.

The good news came on a Monday morning. On May 4, four days after learning that COVID-19 was in their community, authorities in Pond Inlet were informed that the test result had been a false positive. Nunavut was, for now, virus-free after all.

“That was such great news,” says Arreak. He and the rest of the hamlet council had planned a meeting for that Monday afternoon, to discuss the possibility of a curfew and other measures. Instead, the meeting became a more celebratory event.

Technically, the identity of the person who tested positive was supposed to be a secret, but word gets around in a small town, and many people in Pond Inlet had known who it was all along. The community congratulated them by staging an impromptu drive-by procession of the home in question—a long line of Ski-Doos, cars, trucks, and ATVs rolling by, their occupants honking and cheering.

“They kept their distance like required, they did that. But the celebration was on,” says Arreak, who emerged from the council meeting in time to see the crowd. “It was just great. It just uplifted the family.” Fiona Aglak estimated there might have been 100 people in the parade.

“We went to show our love to them,” she says.

The news was a relief not just to people in Pond, but across Nunavut and the North. It was also a reminder not to get complacent. “This was like a preparation for the next one,” says Arreak. “But people responded very well, we complied with all the directions that were in place for us, and we supported the family.”

In late May, nearly a month after the false positive, Fiona Aglak joined the ranks of northern residents tested for the coronavirus. She’d had a few cold symptoms, so she got the test, and then stayed home and away from the radio station until she received her results. Thankfully, they came back negative. “I was told I’m good to go,” she says. Soon, she was back on the air.

As of this writing, the confirmed-case count in Nunavut remains at zero. The five known cases in the Northwest Territories, and all 11 confirmed cases in the Yukon, have recovered, as have the 16 cases in Nunavik. Tentatively, the territories are moving towards reopening. But the possibility of new cases and clusters, the threat of a second wave, still looms.

The scare in Pond Inlet was a microcosm of the North’s broader experience of the first wave of COVID-19. Disaster threatened, and then receded without yet coming into full bloom. That’s something to be grateful for, and to learn from, as we continue to try to keep the virus out of our communities.