Owen Jaworenko likes dogs because they don’t break down like snow machines. On the land around Pond Inlet, Nunavut, a busted snow machine can put a hunter in a deadly situation. A good dog team can save your life. When Jaworenko was 17, he started raising his own team of dogs. He doesn’t want another broken snow machine to leave him marooned and stalked by a polar bear.

Pond Inlet is a small community on the northernmost tip of Baffin Island that faces the fortress of mountains and glaciers of Bylot Island. In summer the waters of Eclipse Sound are often tranquil and punctured by icebergs that sail by the hamlet. In winter, some of those icebergs are frozen in place when the ocean becomes an extension of the land. Hunters travel out on the ice in search of polar bear and seals. Jaworenko is one of those hunters.

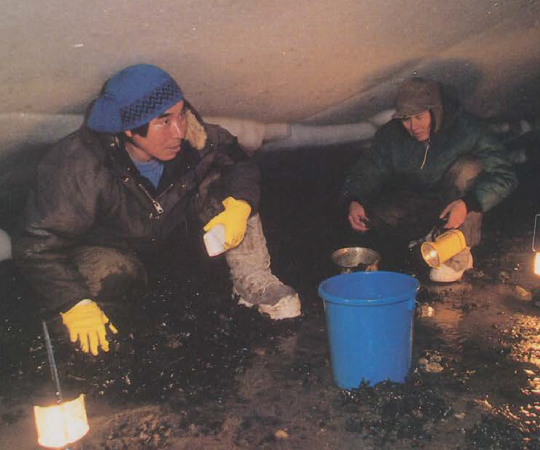

Just over a year ago, Jaworenko and a friend were heading home from a hunt near the floe edge when their snow machine quit. The drive train was trashed and there was no way to repair it out on the ice. It was getting dark and cold and the wind was picking up. There were signs of a polar bear in the snow and they decided they had better hike to a shelter about eight kilometers away. They wrapped their cooler, stove, and supplies of tea and sugar in a tarp and pulled the bundle across the ice from Button Point on Bylot Island to a cabin on the shore of Baffin Island.

What they didn’t know that night was that a polar bear was stalking them. It followed them to the cabin and they could hear it rustling around outside. Jaworenko says they “ignored that bear because we had no tag to shoot it.” They also didn’t know that a search and rescue team was out looking for them and confirmed the bear’s tracks followed their own steps all the way to the cabin. They made it home, a little dehydrated but otherwise in good condition.

Not long after, Jaworenko started raising his dog team. He started with a single female, but he has a few more dogs when we meet just before my own trip on to the ice not long after Jaworenko’s polar bear encounter. The brief sunlight hours in January allow for short trips out on the ice. My snow machine is loaded with trail mix, hot tea and my camera and just as I start out, I remember hearing that someone saw a polar bear in the area the day before. I don’t have my shotgun.

On the edge of town, I pull up to Jaworenko cutting frozen seal with an axe and feeding his dogs. If anyone would know about polar bears, it would be a musher. The adult dogs are tied to anchors in the ice but the puppies run free and play among the seal torsos they’ve gnawed on and hollowed out. Owen looks up from his chores, smiles and says, “Yes, a sow and her cubs were spotted just northeast of town, but I’m pretty sure they’ve moved on. Hunters likely scared them away.”

Jaworenko moves calmly among the dogs, like they are family. His words are deliberate, with a quiet kind of confidence. Before his grandmother died in 2016, she would take him out every spring and teach him survival skills and how to harvest from the land. He took the teachings to heart. He is a good hunter who provides for his family. He left school at the age of 17 to begin building the dog team. He realized that school was not for him. He struggled with academics but excelled on the land. “For me, it’s better to hunt than to stay in town,” he says.

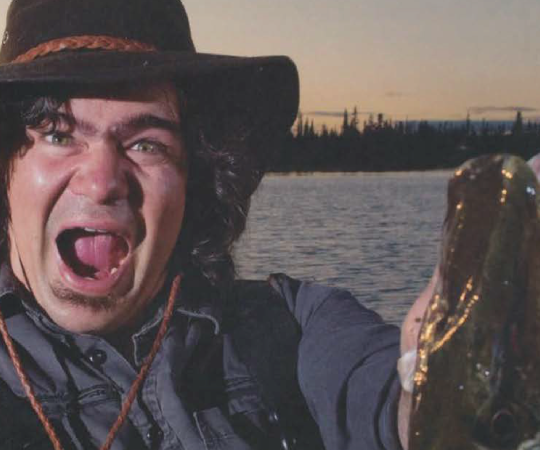

I see Jaworenko again the following September when the water is free of ice and the air is crisp. He has just returned from hunting seal by boat. He is standing outside his house beside a huge plastic bin surrounded by what seems like everyone in Pond Inlet. I peek into the bin and see what I think are several seals inside. Jaworenko says it’s actually a single hooded seal, about 13 feet long and weighing about 900 pounds. “These animals are not common to the waters around Pond Inlet,” he says. Jaworenko and his 18-year-old brother Richard are the first to harvest one in many years. “We found whole thorny skate and turbot in the belly of this seal.” It takes four men to lift the cape from the bin and spread it out for the community to see.

Jaworenko takes me into his home to meet his parents Mary and Rocky, his partner Cheyenne, and son Nathan. Jaworenko, now 19, is quickly becoming a prominent hunter in the community. Other relatives visit to help celebrate the hunt, filling the house with loud laughter and chatter. Mary offers me tea and tells me she is proud of her son.

When the celebration settles down, Jaworenko tells me the bad news. His eyes lower a little and says animal control shot most of his dogs. The dogs were tied by rope and chain to thick ice anchors and posts, but a polar bear came by and excited the dogs so much they broke free while he was away hunting caribou. It’s a setback but he plans to raise another team, he says.

About five months later, I’m back in Pond Inlet. Jaworenko is excited by a new litter of puppies from the lone surviving female. He has moved the dogs up to a sheltered area by his house where they are safe from the dangers on the ice. Jaworenko expects to have the team ready to pull by February 2020. His snow machine is still broken, but he’s happy raising the dogs that will replace it.