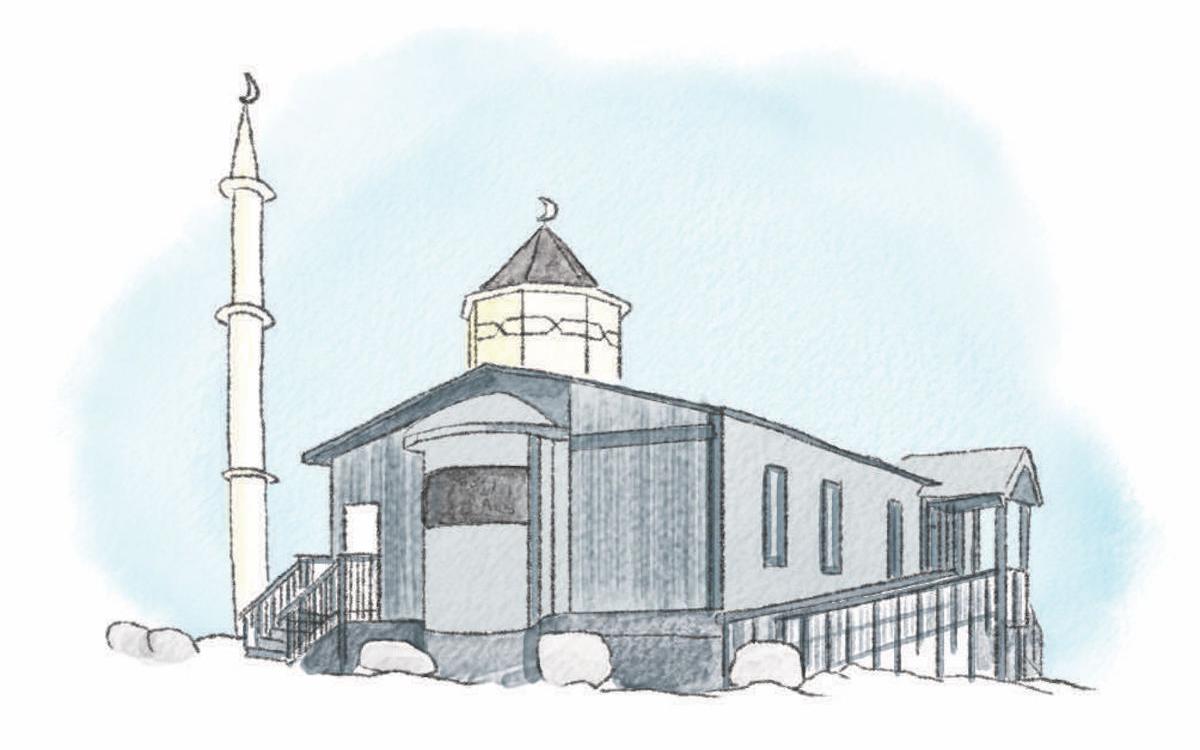

The moment I arrived in Inuvik, on my first visit to the North, I went to see its masjid (also called ‘mosque’). It was mere months before the highway to Tuktoyaktuk opened to the world. Pedaling my bicycle on Wolverine Road, I didn’t know what to expect from the world’s most northern mosque. A small house? Similar to the humble beginnings of other masjids in the south? Really, almost anything but what I saw. A minaret, a symbol of the call to Islamic prayer. Here, at the end of this new road, there was a sanctuary for us. Here, we Muslims mattered.

The first time I landed in the North it had been about 15 years since initially arriving as an immigrant to Turtle Island. I cycled to Inuvik, all the way across the country from the Atlantic Ocean. If the first 10 years in this place were filled with gratitude, the following decade has been a painful unlearning of the clean narrative of Canadian history. Of learning to question what is “Canada.” To question who was forced into unhonoured treaties, while their ways of life were, still are, brutally (or quietly) suppressed.

The second time I came North, it was on an invitation to Whitehorse. I flew instead of cycled. I accepted a job with a youth non-profit that does work across the territory, northern British Columbia, and in the Mackenzie–Beaufort Delta. I had been dreaming about coming back since my first visit, to continue learning about this corner of the continent. Could I have dreamt about the friends I’d also make in Fort McPherson, Inuvik, and Mayo? That I’d get to spend a week in Old Crow, or meet the mayor of Iqaluit? Reality, if we listen well, writes a better script than our imagination.

Frank Turner, the Yukon Quest winning musher, told me years ago at a restaurant that the way of the North is built on relationships to each other. Bobbi Rose Koe, a guide and leader of her people—the Teet’it Gwich’in—and this place, constantly reminds me that those relationships extend beyond the ones between humans.

Even for someone who is precisely me—brown, Muslim, immigrant—there are physical reminders that my people are here. The Muslim community in Whitehorse is not large, almost small. But it is also not new. Some of the members have been here for three decades and counting. The scale of the community (as opposed to the geography here) means that unlike other mosques, there is no staff person. So someone such as myself, who at times has drifted from organized religion and is in constant renegotiations with the Creator, gets to volunteer and give the weekly jumu’ah sermon. This has happened five times pre-COVID. My favourite verse from the Qur’an is one I am daily reminded of with the natural splendour of this place:

fabi ayyi ala i rabbikuma tukazziban

فَبِأَىِّ ءَالَآءِ رَبِّكُمَا تُكَذِّبَانِ

(Which, then, of your Creator’s wonders do you deny?)

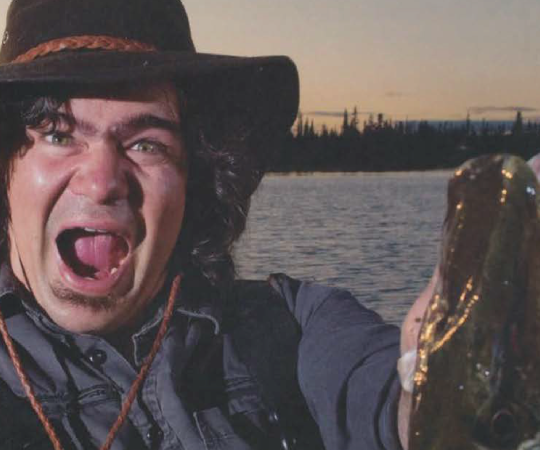

The third time I arrived in the North was with my cousin, Christopher Tse. This time, we drove from Squamish, Stó:lō, Səílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh), and Musqueam Nations lands (also known as Vancouver). It took almost three full days and there was a real poetry to returning here, together. The first time I cycled North, Chris was driving south. Somewhere on the Alaska Highway, my cousin and I met. He refilled my water bottles, and fed me grapes and salmon jerky. Then, we parted ways, at least geographically.

What does it mean to call a place home? What does it mean for a place to call you home?

A three-year old here, the son of artist Lianne Marie Leda Charlie, has been teaching me. It is to know the older names of these places in more ancient languages. When I see the Tagé Cho (Yukon River) now, I feel like I am seeing that minaret in Inuvik, all over again.

For more than four seasons now, every single day, I have called this territory of Kwanlin Dün and Ta’an Kwäch’än home. It is the longest I have lived anywhere in almost a decade. If I go anywhere, it will be further North.