The North has many things to offer to the people living here—amazing neighbours, breathtaking landscapes, a culture deeply rooted in both the arts and an outdoor lifestyle—but until this past spring, a university education wasn’t on the list.

Canada was the only circumpolar country without a university institution north of the 60th parallel. Northerners who wanted a university-level education had to go outside to get it, which often meant travelling thousands of kilometers away from their families, friends and the culture and lifestyle they grew up in. Even if Northerners wanted to study about the North, they had to learn at southern institutions.

“I always wanted to live and work in the North, but I had to learn about the North in the south in order to be able to get my credentials,” says Lacia Kinnear, executive director of governance and external for Yukon University (YukonU).

She wasn’t alone. Northerners have, for years, had to go south for post-secondary degrees. Now that’s all changing.

Last spring, Yukon College officially became YukonU. Five months later, the Government of the Northwest Territories (GNWT) released a transition plan outlining how Aurora College will make the leap to becoming a polytechnic university by 2025.

Plans for the transitions go back decades. Both the Yukon and the NWT have studied, proposed, crammed and lectured about how to transition their respective post-secondary institutions into the first university institution north of 60. Those plans are finally becoming reality.

Now, not only do bright, young Northerners have the option of staying in their home territory to study, but southerners will also have the option of learning about the North, in the North, from Northerners. In a few short years, Aurora College’s transition will expand those options further.

The potential to dramatically alter the northern educational landscape is huge. Training Northerners for jobs at home could improve the labour market and economic prospects of the territories. Providing a home for academics and researchers could reverse the northern ‘brain drain’ to the south.

“This (transition) creates the opportunity for people to come and learn in the North from Northerners,” says Kinnear. “It also allows us to be able to attract investment through fundraising, and also through research dollars to really increase that northern capacity to answer the questions and to develop the skills and training necessary for what the North needs.”

Both schools have different goals and approaches to their university transitions. YukonU’s first year has in some respects been a write-off, at least in terms of how it expected that year to go (thanks, COVID-19), while Aurora College’s future is still more questions than answers at this point. Whether or not the new institutions can live up to their lofty aspirations remains to be seen.

Transitioning from a college to a university is a big job, and doing so in the middle of a global pandemic has definitely not made it any easier for YukonU.

The university has had to focus heavily on making the switch to online offerings and managing the COVID-19 crisis on campus, and this has meant major shifts in thinking, personpower and workflow. Online courses had to be set up for teachers, students, and support staff. Plans needed to be built to keep everyone safe and healthy.

This has not always been easy. When the campus opened for its fall semester last year, it almost immediately fell back into restricted access protocols following the discovery that two non-Yukon students had moved into student housing without undergoing the mandatory 14-day quarantine.

COVID aside, the sudden departure of its first president, Mike DeGagné, didn’t make the university transition any easier. DeGagné, who had previously been president of Nissiping University in North Bay, Ontario, came on as head of YukonU in July 2020, only to jump ship two months later and take a job as CEO of Indspire, an Indigenous-led-and-focused charity based in Ontario. Vice-president Maggie Matear is still serving as interim president.

All in all, YukonU’s inaugural year has clearly presented some unforeseen turmoil. What really matters most, of course, is how the students feel about the transition.

Maegan McCaw, now a conservation coordinator with the Yukon chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS), graduated last year from the environmental and conservation science degree program (run by the University of Alberta, but offered at YukonU with a focus on northern ecosystems). She was a student during the transition from college to university and says she’s happy she took the program through YukonU, instead of going south. “We got to have such a narrow focus on northern systems [in the YukonU program] and to work with instructors that often have a full-time job in the field they’re teaching,” says McCaw. “I thought that was really valuable… and, of course, the nice, small class sizes.”

The transition did cause some stress for Torey Hampson, who is studying social work (a program delivered by YukonU for the University of Regina), because it was unclear if some of her courses would be transferable to her parent university.

“In the eyes of [the University of Regina], YukonU was totally different from Yukon College,” she says. The University of Regina had pre-approved her mandatory courses, but the electives were up in the air after the switch. Still, Hampson says professors were “very generous” in helping her make sure her credits would be transferable, and that process has since been completed and all her credits will be counted.

Aside from that, very little has changed for her in her studies.

“So far, it’s been excellent,” she says. “I haven’t noticed (the transition) too much, which is probably a good thing; it means they’re making a transition that doesn’t hurt students.”

Over the territorial border in the NWT, however, the transition to a university system has been a little rockier. Aurora College is currently in the midst of a three-staged plan for becoming a polytechnic university. The first, “Strengthening the Foundation,” has been under way since 2018 and involves updating policies and procedures to lay the groundwork for a new post-secondary system in the territory. As part of that work, the GNWT and the college recently identified its areas of academic specialization for the new Aurora University, with plans for a three-year strategy to be released in August and legislative changes to the Aurora College Act (ACA) expected to be put forward in October 2021.

Phase two will adjust the college’s organizational structure and put together an academic council, as well as dump the old ACA for an entirely new piece of legislation. That’s expected to take until the end of 2024. Phase three begins with the launch of the new polytechnic Aurora University in May 2025.

So, still a while to go. One of the reasons for the lengthy transition process seems to be Aurora College’s tight—and fraught—entanglement with the GNWT. Take the ACA, for example. In a 2018 foundational review of the college by national consulting firm MNP, it was found that although the current Act says the relationship is supposed to be “arm’s-length,” this was not actually how the school was operating. Under the Act, the institution is supposed to be run by a board, where members are appointed—and can be removed—by the education minister.

YukonU, on the other hand, is governed in that territory by the Yukon University Act, which took effect last February. It has been an arm’s-length institution (as Yukon College) since 1988, although the minister of education retained the right to approve tuition and fees until 2009, and the Yukon Government (YG) still has veto power on 10 of the university’s 17 board members.

Aurora College’s board was dissolved in 2017, something the review report notes happened as a result of an administrator not being appointed, rendering it “ineffective.” The report also noted the relationship between the department of education, culture and employment (ECE) and the college had been “characterized as ‘challenging.’”

In its response to the foundational report from 2018—which the GNWT noted proposed a system of governance “very different” from the one Aurora College had been acting under—the territorial government agreed that in order to succeed, the polytechnic university that the college is to become must indeed function at arm’s-length—something which had previously “not been achieved.”

For Aurora College-cum-polytechnic, that sort of governance model would promote academic freedom and institutional autonomy. It’s also of unique importance in the NWT because of the political concerns that circulate around the transition plan. Rebbeca Alty, mayor of Yellowknife, has criticized the lack of social science courses to be offered at the new institution. Talk of potentially consolidating the institution's three campuses to Yellowknife has also left residents in Fort Smith, presently home to the school’s Thebacha campus, concerned over impacts to their community and economy.

A polytechnic university differs from a standard university in that it focuses on applied, hands-on learning, while still teaching applicable theory. It exists in a sort of no-man’s-land between community college and university, with a focus on employable skills. Given that nearly a quarter of Aurora's student body was enrolled in adult literacy and basic education in the 2016-17 academic year, and another 14 per cent enrolled in a trades program, it’s clear this choice plays to both the current strengths of the college and the needs of its students.

Successful employment for Northerners is the main priority for the future school, says Chris Joseph, ECE’s Aurora College director, with future decisions around specialization and programming responding “directly to labor market demand.”

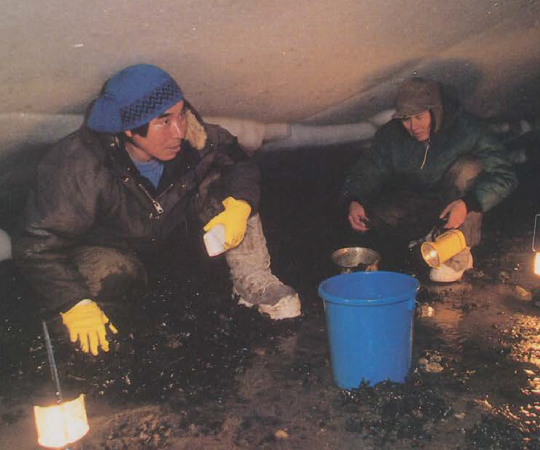

To that end, Aurora College has identified four key areas for future programming: skills and trades; resource and environmental management; northern health, education and community services; and business and leadership. With its employment-driven objectives, and the resource-heavy nature of the Northwest Territories’ economy, (not to mention the need for remediation workers to clean up messes left by projects such as Giant Mine), it’s easy to see why the school has chosen the route it has.

By contrast, YukonU has adopted a ‘hybrid’ model, aiming for both a more academic and research-based approach to post-secondary education. Its goal is to offer programs about the North, taught by Northerners, for both Northerners and southerners, even as it maintains its traditionally trades-heavy roots, says Kinnear. Given that 48 per cent of students who attended Yukon College in the years before its transformation already had post-secondary experience and 30 per cent already had some type of trades certification, moving to a more academic model makes a lot of sense for the fledgling institution.

These choices are reflected in the first two YukonU-specific degree programs the institution put out in its inaugural year: a bachelor of arts in Indigenous governance, and a bachelor of business administration with a northern focus. A bachelor of arts in northern studies is expected to be on offer later this year.

“We knew early on in our university journey, that we weren’t going to be a university that would do everything for everybody,” Kinnear says. “We very specifically decided that we were going to hone in on northern-focused programming.”

This northern-focused research model is not without precedent, and being in the High North—which means dealing with the remoteness and lack of jobs that can lead to a “brain drain” to the south—need not be a barrier to being a world-class institution. Our American neighbours have the University of Alaska system, with three major university campuses and a dozen college campuses scattered across the state. In Norway, the University of Tromsø—the world’s northernmost university—is a well-respected institution specializing in Arctic research around areas like auroral light, space science, and studying Sámi culture.

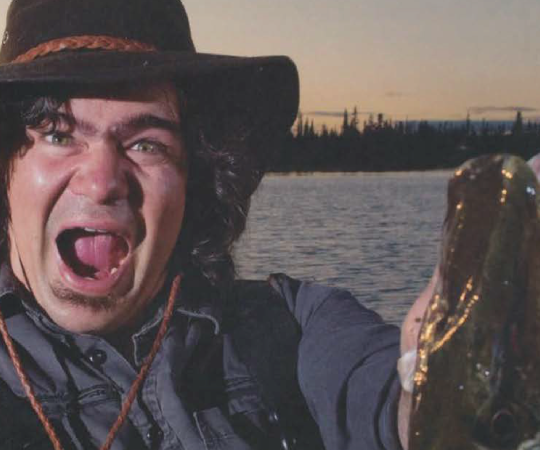

It’s a bit too early in the game to see the long-term benefits of having a homegrown institution for Northerners in Canada, but possible outcomes include more Canadian-North specific research—especially Indigenous-focused and led—which is something YukonU is trying to focus on, says Kinnear. Take, for example, Zhùr, the mummified Ice Age wolf pup carcass unearthed from the permafrost outside of Dawson City. Zhùr made international headlines and gave a massive spotlight to the work being done by Julie Meachen, who led the project from Des Moines University—a southern institution. Wouldn’t it be optimal to have Yukon-based research led by Yukoners?

“The real opportunities [for northern universities] are going to come with increased abilities to collaborate and connect,” says Brian Horton, manager of climate change research at YukonU’s Research Centre and lifelong Yukoner. “My lived experience was having to leave the territory to go to university. It’s super exciting that that’s no longer going to be necessary.”

Taken together, both YukonU and Aurora College have very different approaches and goals to their transition and programming—and that’s probably a good thing. Ultimately, having not only one but two northern-focused university institutions in the territories means more education and employment options, and more truly northern voices in the ivory towers of academia, both at a national and international level.

“There’s so much richness and so much knowledge in the North,” says Kinnear. “Having a university here puts us on the same platform as the rest of Canada. It brings our northern voice to the table.”