When Manitok Thompson was hired to build the Inuit Broadcasting Corporation’s archives seven years ago, she knew a colossal task lay ahead of her. The organization had amassed 9,000 hours’ worth of newsreel, television shows, and footage shot across Nunavut since the late 1970s—and all of it needed to be cataloged and digitized for the virtual age.

For Thompson, that meant long days in front of a screen at the IBC headquarters in Ottawa, watching her way through endless boxes of tapes and scribbling down what she saw for the records. It was a big job—but not a tedious one. Because as Thompson watched, an entire world unfolded in front of her eyes.

“It just boggled my mind,” she says.

The tapes were a rich encyclopedia of Inuit culture and language. Coverage captured the territory’s entire political history—from the signing of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement in 1993 to the creation of the territory in 1999. But most of the footage documented everyday Inuit life: hunters travelling by dogsled; families preparing and eating seal meat together; mothers sewing amautiit; Inuit carving snow blocks to build igluit, and everyone speaking to one another in Inuktitut. There was a how-to on navigating the land, on Inuit birthing practices, on tanning caribou hides. One of Thompson’s favourite clips was an interview with an Elder from Kugluktuk, recounting the first time she tried candy at the local trader’s house. (Apparently, she wasn’t a fan. “She spit it out, she had never tasted something so sweet,” says Thompson.)

Thompson, originally from Coral Harbour, often found herself speechless after a day of work. “I would be watching these shows, and I would be laughing, I would be crying, I would get emotional,” says the former cabinet minister from both the pre-division NWT and post-division Nunavut. “I understood it so well as an Inuk. I was thinking to myself, ‘This is a gold mine. These stories are worth more than gold or diamonds in our culture. And it’s all recorded.’”

This year, the Inuit Broadcasting Corporation celebrates the 40th anniversary of its first-ever broadcast. To this day, it’s considered by many to be the vanguard of Indigenous television in Canada, born in a push to save Inuit ways of life from the insidious (and overt) encroachment of southern culture in the late 20th century.

“Television was invading our homes,” says Peter Tapatai of Baker Lake. By 1975, nearly every living room had a set, and it broadcast a steady stream of English-language programming. The lure of the screen quickly changed the social fabric of Northern communities, as popular shows like Sesame Street and Mr. Dress Up pushed the Inuktitut language and Inuit values to the background.

“It was dominating,” Tapatai says, “For our culture and our language to survive, we needed to find ways in every avenue to protect [them].”

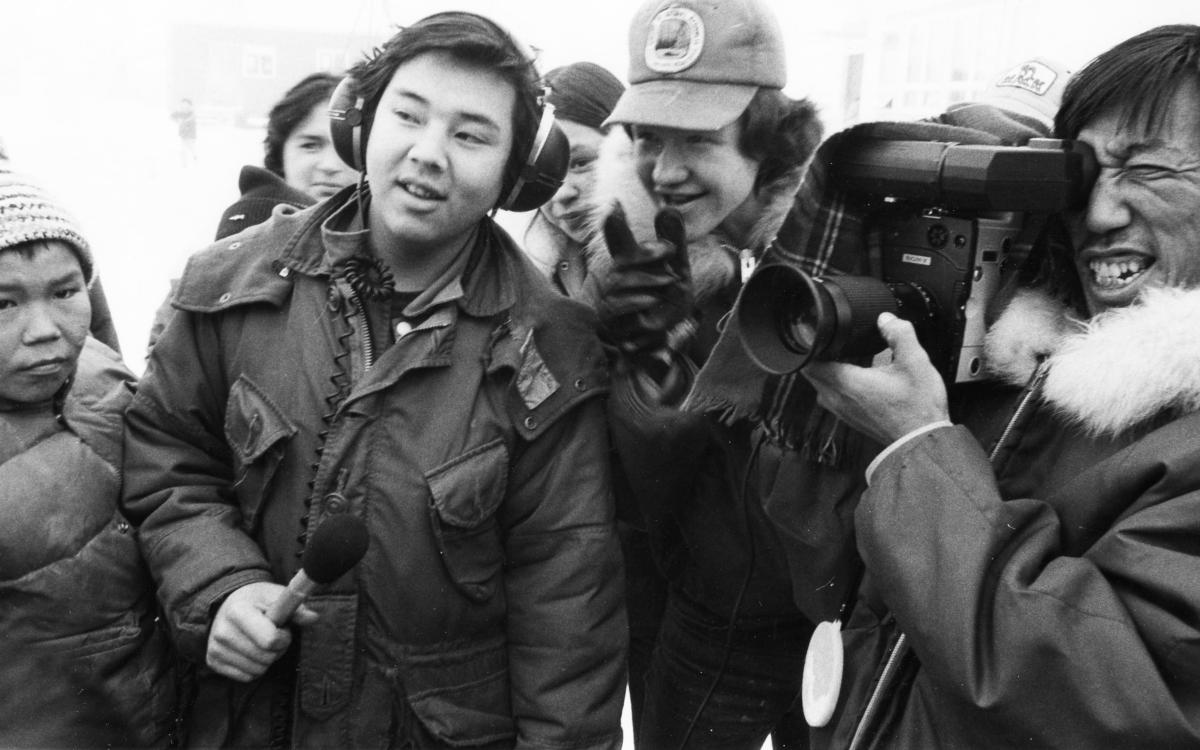

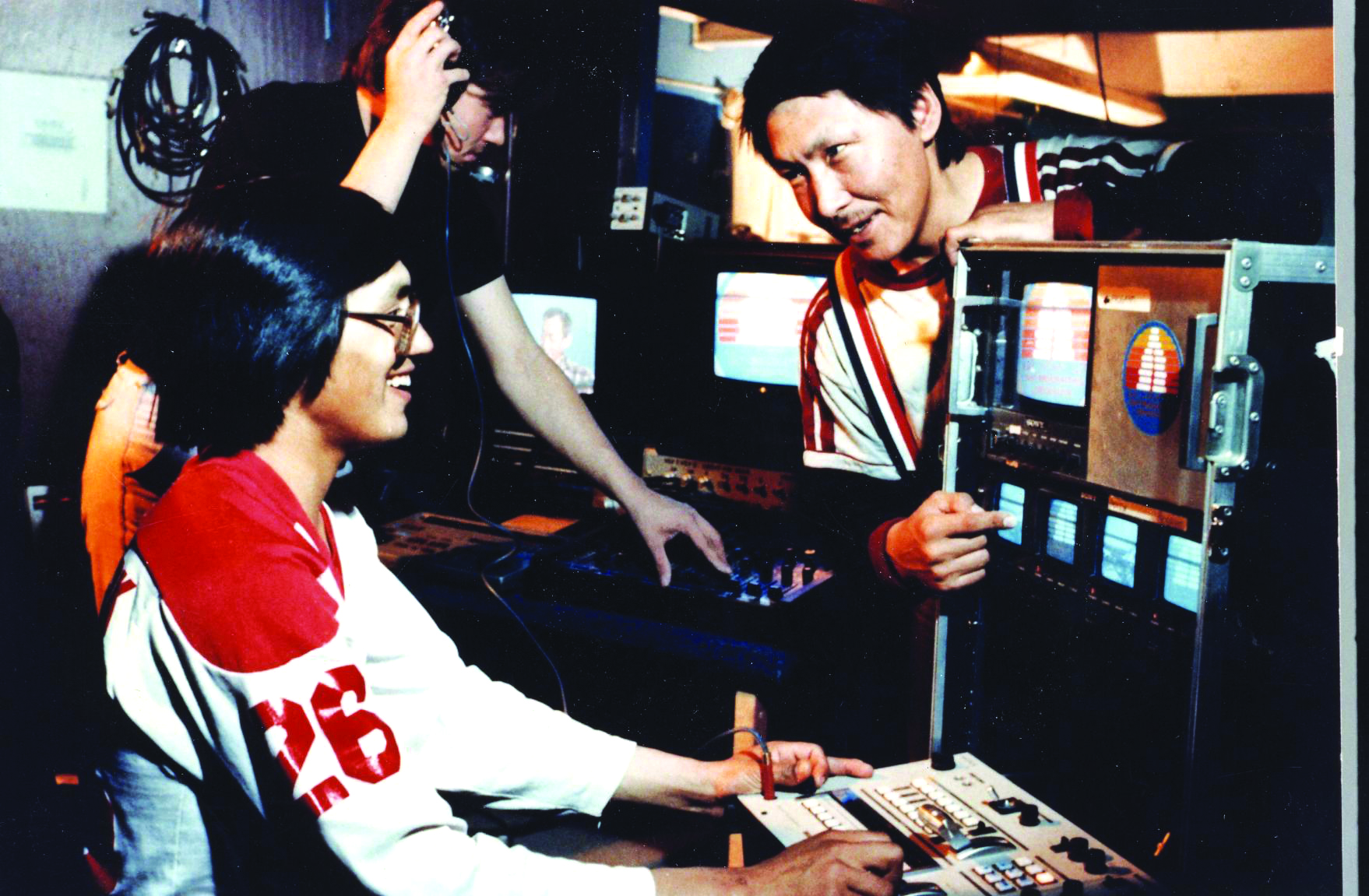

In search of a solution to this existential problem, Inuit Tapirisat of Canada (now called Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami) devised a two-year pilot called the Inukshuk Project in 1978. It established facilities in six communities (Iqaluit, Pond Inlet, Iglulik, Baker Lake, Arviat, and Cambridge Bay) and trained Inuit in television production. The facilities began broadcasting via satellite from Iqaluit in 1980.

The pilot project was a rousing success and it proved two key things: Inuit communities were viable bases for budding communications technology in the Arctic, and that Inuit were more than capable of producing programs for their own people. The CRTC granted Inuit Tapirisat of Canada a broadcasting licence in 1981, and the Inuit Broadcasting Corporation was formed. Within a year, it was airing regular programs.

For those who were there, these early days still hold a place of rosy reverence. It was a new frontier, one where Inuit had taken power back and now had the space to bring their own stories and people to the screen. The doors of possibility had been flung open.

Amongst that first cohort of Northern television producers was Zacharias Kunuk, the Iglulik-based filmmaker known internationally for his 2001 feature, Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner. He was hired by IBC in 1983 and spent the first eight years of his career at the Iglulik bureau bouncing from camera operator, to sound editor, to scriptwriter—a true television everyman.

“I used to film everything,” he says. He remembers crashing many harvests with his camera in hand. From behind the lens, Kunuk would watch as hunters shot walrus and seals, then expertly skinned and butchered them. Their knowledge of the land and water was incredible to witness.

“We’re two hours out on the sea, no land in sight,” he says. “If I went alone, I would never get home. But the hunters knew how to navigate using the sun. I was amazed.”

Tapatai was also there in the beginning, producing and hosting shows in the Kivalliq region. He’s best known as the beloved Inuk hero Super Shamou, who uses his power of flight to watch over the North, keeping Inuit safe on the land, and encouraging healthy habits and choices.

“I never imagined it to be so popular, even to this day,” Tapatai laughs. “My goodness, I’m ready to retire and there are children that are still asking me about it.”

But that’s the power of television, he acquiesces. It’s a medium with staying power, with the potential to devastate a culture or give it new life and carry it forward for future generations.

“We were able to reverse what was invading our home into something positive,” Tapatai says. It’s a legacy felt in the shows IBC continues to create today—Takuginai, a children’s program that teaches Inuktitut; Niqitsiat, a cooking show that focuses on country foods; Qanuq Isumavit?, a live production where people can call in to discuss current issues and events. All produced for, by, and about Inuit.

And the biggest piece of that legacy, Tapatai says, are the recordings of Elders and knowledge-keepers that now reside safely in the IBC archives. “A lot of the Elders in my community have long gone and passed away. And if we did not have the Inuit Broadcasting Corporation, if we did not take that initiative at that time with the Inukshuk Project, we would have lost a great deal more.

“I’ve always been very, very grateful that we had the ability to do that—to preserve our Elders’ stories.”

Over the past forty years, the IBC has weathered a continually morphing Arctic television landscape. It was part of the coalition that launched the Television Northern Canada channel and laid the groundwork for what became the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network, where it continues to air Inuktitut programming today. While most of the smaller IBC bureaus have shuttered, the studio in Iqaluit has expanded, with a brand new, state-of-the-art media centre unveiled in 2015.

In Ottawa, Thompson now serves as the organization’s executive director, where she leads the fight for more funding and opportunities to increase Inuit representation on screen. She’s currently exploring the creation of a mentorship program for Inuit youth to learn video skills, and has negotiated a partnership with SSi Canada, a Yellowknife-based telecommunications company, to allow anyone with a Smart TV or phone to access the video archives.

Because Thompson wants other Inuit—and everyone, really—to experience the same feelings she had watching that tape. “These archives show it all,” she says. “It’s our treasure.”