Rain ribboned the windows of Yellowknife’s airport terminal building, as 21-year-old Jamie MacDonald—stylishly dressed in pressed blue jeans and a Tommy Hilfiger jacket—ventured outside and sloshed towards the Buffalo Airways hangar. It was May 2018, and carrying a commercial pilot’s licence—and not much else—MacDonald had left a comfortable Toronto home to try to join the ranks of Northerners hauling bulk cargo to communities beyond Great Slave Lake.

She arrived without promise of employment, but upon meeting MacDonald, airline owner “Buffalo Joe” McBryan and chief pilot Anthony J. Decoste sensed the potential entrant’s commitment to their fast-paced world. Still, first-timers often scuttled back to milder climates as soon as the snowflakes fell. In spite of their doubts, they added MacDonald to the payroll.

MacDonald’s passion for things with wings originated with her great-grandfather’s World War Two logbook. The yellowed pages spoke of Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) rear air gunner George Joseph MacDonald’s tribulations in a four-engine bomber called an Avro Lancaster. Not much older than a teenager, he persevered through 36 perilous missions in hostile wartime skies and came home alive. “Little Jamie” never met her great-grandfather—the former flight sergeant passed away in 1959. Nevertheless, his courage and devotion to duty inspired the child as she fingered the logbook’s hand-printed numbers and city names like Essen, Dortmund, and Wiesbaden among pages of crackled photographs.

But MacDonald didn’t pursue a career in aviation right away, electing instead to enroll at York University to become an elementary school teacher. During a study break, MacDonald wandered into a nearby flight centre for a sample flying lesson. Before the tiny training airplane’s rubber tires scuffed the asphalt again, she knew what had to be done. She signed up for a commercial pilot course, with dreams of piloting a Lancaster—just like her great-grandfather. “I didn’t know when and I didn’t know how, but I’d fly one someday,” she says. (There are only two airworthy Lancasters today. Hamilton’s Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum (CWH) restored one that used to fly over MacDonald’s Toronto home when she was a child.)

Three years later, she had gained her commercial licence. She thought about becoming a volunteer pilot with the CWH, but recognized she’d need more experience. Around that time, fellow flying school graduate Mike Corazza described his new position as a Buffalo Airways co-pilot and encouraged MacDonald to apply. MacDonald knew Buffalo received resumes from all over the world since the popular Ice Pilots NWT reality TV show took to the airwaves. Aware of intense competition, she decided to take a chance and invested in an airline ticket. “I’d applied for jobs everywhere but with Buffalo, it might be possible to fly World War Two vintage airplanes,” she says. “Yellowknife was farther north than I’d ever been and probably colder, with a higher cost of living, but it was worth a try and a good way to explore my own country.”

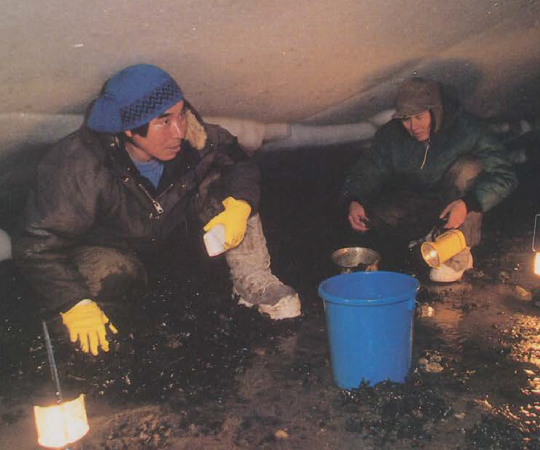

MacDonald accepted an apprentice-like position as a “rampie”—or future co-pilot. Ground assignments proved far more demanding than wiping windshields. Pallets packed with epicurean delights such as Mr. Noodles for Kugluktuk, Nunavut, awkward snow machines or boats expected in Tulita, or generators manifested to Paulatuk all meant cautious lifting and adroit manipulating in summer blackflies and winter’s frosty air.

When not brushing hangar floors amid squealing brakes and hissing hydraulics, MacDonald walked the innards of a classic twin-engine freighter called the Douglas DC-3, which dwarfed anything she’d flown before. The “Grand Old Lady,” as aviation aficionados know the 1935 design, had played important roles in World War Two; great-grandfather George Joseph would have watched them crossing the English Channel. To MacDonald’s delight, operations manager Jeff Schroeder assigned her to DC-3s. After training and air testing, she found the huge aluminum-skinned airplane quick to respond but gentle.

MacDonald then set her sights on a larger Buffalo airplane known as a Curtiss C-46, which carried twice the DC-3’s cargo. Aircrew warned the ponderous “Calamity Curtiss” could be tricky: the colossal transport depended on a tailwheel similar to the DC-3 for ground steerage instead of an easily manoeuvrable nosewheel apparatus typical of modern jets. C-46s have swerved off airstrips and runways due to crosswinds, unequal control pressures or pilots relaxing their firm grip on the controls too soon after landing. Pilots require prompt action and exceptional skill to bring the giant of the North safely home.

Some chauvinistic experts suggested the physical handling of a Calamity Curtiss might exceed the capabilities of a woman pilot. Decoste and McBryan disagreed. On August 4, 2018, MacDonald tested successfully under the watchful eyes of Schroeder, who happened to have more C-46 experience than any pilot in North America. When she silenced the three-blade propellers, MacDonald had unknowingly created history by becoming the only female C-46 pilot in any country to hold both current C-46 and DC-3 ratings on a commercial pilot licence.

“I never sought the recognition. All I wanted to do was fly and considered the C-46 as another step toward a Lancaster,” she says. “Although the C-46 may be challenging, I’m being coached, monitored and encouraged by professionals and every time the throttles go forward, I learn something.”

Each flight provides the opportunity to experience something new, with MacDonald safety-belted in the flight deck, in aircraft where onboard heaters provide meager comfort and freight reeks of aromatic paint cans, over-ripe groceries and snugged-down fuel bladders. “Consignments to the Sahtu or Nunavut regions like the Kitikmeot or Kivalliq are never routine,” she says. Runs down the Mackenzie River valley are common. “We drop into historical sites like Fort Franklin (Deline) where Sir John Franklin wintered, and Fort Norman (Tulita) where the Hudson’s Bay Company put a post in 1810. Everything that goes aboard out of Yellowknife’s important, whether it’s food, coiled mine cables or time-sensitive Buffalo Express packages.”

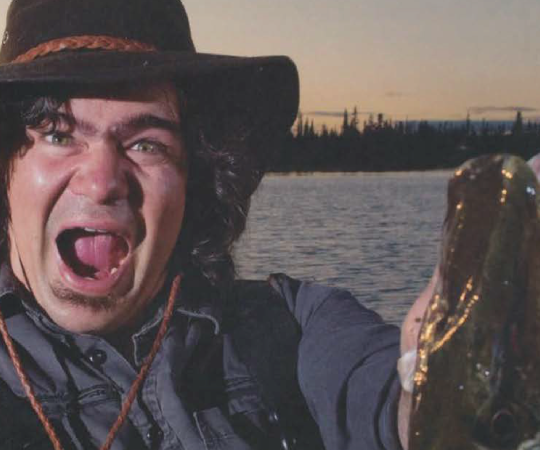

Although space remains for the Lancaster in her pilot logbook, Yellowknife has come to feel more and more like home to MacDonald. She enjoys the off-duty camaraderie with fellow pilots and mechanics, who cluster at ‘cultural centres’ like the Black Knight Pub or Gold Range Saloon. And she relishes any chance she gets to head out on Great Slave Lake to hunt trophy trout.

She admits she will eventually apply to major carriers for a place in international jets, but plans to stay in the NWT capital permanently. Whatever changes come her way, the rampie who never scuttled southbound when snowflakes powdered her parka, appreciates life North of 60.

And, at least for now, the Avro Lancaster will have to wait.