The old-timers still remember the summer more than 20 years ago that Alan Read disappeared. In Yellowknife’s small prospecting community, everyone knew Read. He was tall, British, nearly blind, and eccentric – the kind of guy, as Walt Humphries remembers, “who would paint himself in the corner of a roof and then couldn’t get down.”

Humphries, a long-time prospector himself, recalls the time Read was working on a forestry tower, keeping a fire-watch. He’d been given a two-way radio, but for some reason he stopped checking in. A helicopter was dispatched to the tower and, as it landed, Read approached carrying a cardboard box. Inside were the remains of the radio. He’d dissected it to figure out how it functioned, then couldn’t reassemble it. “Here,” he said, handing it to the pilots. “It doesn’t work.”

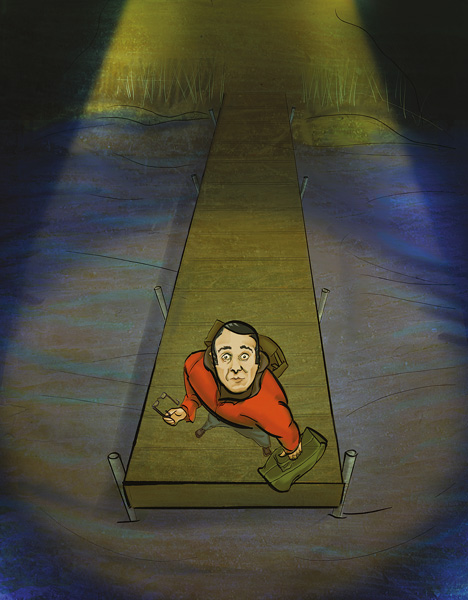

Still, Read knew his way around the bush well enough to feel confident about spending a summer prospecting at Arseno Lake, a remote Northwest Territories spot where he planned to live in a cabin and stake a few claims. A floatplane dropped him off at the dock, then left.

A few days later, a group of prospectors happened by his cabin, only to make a strange discovery. Read’s belongings were still in his cabin, unpacked. But Read himself was missing. When a search of the area found no sign of him, the RCMP were called. They sent divers to search the lake and dispatched teams throughout the woods. But Read had disappeared.

Had he been eaten by a bear? Had he drowned? Had he become lost in the woods without his glasses? No one knew. Stranger still: That same summer, a woman disappeared from an NWT lodge. After a similar search turned up nothing, the locals started talking. “We always thought a UFO picked both of them up and they’re out there in outer space representing the human race,” Humphries says.

He’s only half-kidding. In the vast expanse of the North, the unusual, puzzling and downright mysterious are as common as jackpine and wind. The Northern landscape is a repository of secrets, held buried beneath the snow. In a place where the best efforts of humans often fail, it’s always been so. This issue, Up Here rounds up some of the strangest tales of disappearance in the high latitudes.

The overloaded sled

An Arctic novice, he set out for points unknown—and didn't come back

Hans Kruger was not an especially likeable man. He was, in the words of a one-time travelling companion, a man who “thinks too much of himself” and spoke like “a spoiled child. … I should not be surprised if there were serious trouble.”

The writer was referring to Kruger’s madcap plan to become an explorer. A Prussian born in 1886 in what is now Poland, Kruger had studied arts and literature, managed a Namibian game-farm, and then discovered the two tastes that would cement his fate: an interest in mining and a fascination with the writings of Canadian Arctic explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson. He decided to set off on his own mineral exploration of Canada’s North.

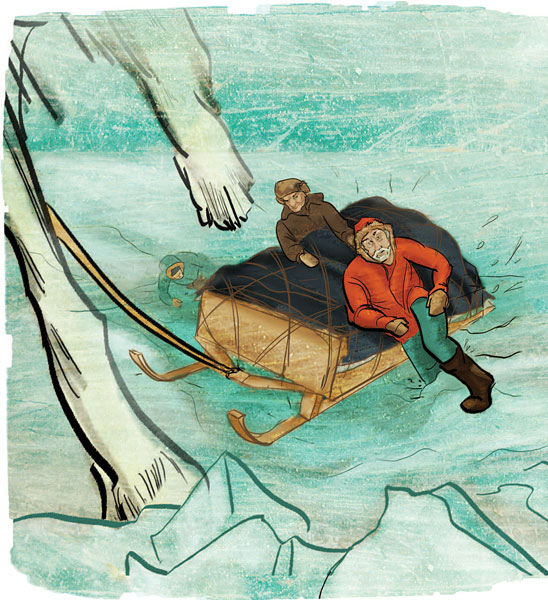

Along with an Inuit guide and a Danish trapper, Kruger started out from Greenland – where he contracted trichinosis, an intestinal parasite – in 1930. Pulled by dogs, he crossed to Ellesmere Island, where he arrived at a remote RCMP outpost on the island’s west coast. He looked like a failure in the making. Still weak and vomiting from the trichinosis, he was hardly in the hale state required for polar exploration.

It didn’t seem to matter to him. After two weeks with the RCMP, he left for Axel Heiberg Island and the western fringes of the Arctic archipelago.

It was an epic trip made all the more so by Kruger’s inexperience and questionable judgment: As he and his crew departed, their sled was so heavily laden that not even their 15 dogs could pull it without human help.

Kruger had planned to return to the RCMP outpost by the summer of the following year. When he didn’t, the officer there set out to find him. It was not until 1932 that he discovered a note Kruger left in a cairn on the northern tip of Axel Heiberg, stating that he intended to continue west to Meighen Island. But traces of Kruger himself, and his companions, weren’t found.

Clues to the mystery, however, continued to surface. In 1957, a note was discovered that proved Kruger had made it to Meighen Island. And just a decade ago, scientists on Axel Heiberg Island discovered remnants of a canvas tent, a compass, an unopened tin of food and some rock samples.

Their conclusion? Kruger must have cached the goods there, on his return trip to Ellsemere, in a desperate attempt to lighten his load. He may have fallen through the ice, or died from illness, starvation, or a bear attack. It’s unlikely his final fate will ever be known.

The angry sea

On one of Nunavut's busiest shores, the ocean giveth—and taketh away

On the distant upper reaches of the North American mainland, Emile Imaruittuq, an Inuk from Igloolik, could remember the day his father looked out across the angry waters of Ikiq and said ikiq ikkirngaasit inugulittualuungmat. Ikiq, according to his father, was once again yearning to claim a human life.

It would not be the first time, nor the last. Of all the places in the Arctic that have swallowed people, Ikiq stands in the memory of Inuit as a sort of Bermuda Triangle, a place where tragedy and mystery have concentrated. Known today as Fury and Hecla Strait, Ikiq is a narrow waterway where fast-flowing currents haunt the short stretch between the Melville Peninsula and Baffin Island.

Those currents bring nutrients that attract an extraordinary abundance of marine life. The water moves quickly enough that even in winter, open-water polynyas serve as perfect hunting spots for walrus, seals and other animals. For millennia, Ikiq has drawn Inuit to the area that is now Igloolik.

But through all those years, the life-giving waters have also pulsed with a dark undercurrent. The currents make the ice thin and unstable. Many men have gone hunting here and never returned, leaving no trace. Inuit shamans used to say that, from the time the world was created, Ikiq claimed so many lives that if the victims’ clothes were laid side by side you would not see the end of them.

Tragedy befell hunters here in myriad ways. Imaruittuq’s grandfather once went hunting walrus on Ikiq. As he and a group of hunters moved about the moving ice on foot, one discovered that the crotch of his pants had ripped apart, leaving him with frostbite. Not wanting to slow anyone else down – or risk their survival – he urged the others to leave alone him on the ice to die, his body joining the many others who would never return.

The lone walker

In love with her mother Russia, she vowed to get home—or die trying

Lillian Alling was a domestic servant in love with her Russian homeland. Trouble was, she lived in Vancouver – or, depending on who tells the story, in New York, or somewhere else in North America. No matter: In 1927, she decided to travel back to Vladivostok. Lacking money for steamship-passage home, she decided to walk. She planned to trek to the top of the world, crossing the Bering Strait to Siberia on her own two feet.

That’s how she ended up in Hazelton, in northern British Columbia, in September of that year. The first blizzards had already descended on the region, yet Alling was determined to go on. To save her from herself, the local police constable stopped her the only way he knew how: He jailed her. But a winter behind bars failed to suppress Alling’s ambitions. The next summer she set off again, following the Yukon Telegraph Line north.

Word of her journey proceeded her, and the stories – some no doubt apocryphal – began to multiply. A telegraph linesman gave her a dog and it was said that on the coldest nights she slept with just the dog for warmth. On the hardest parts of the trail, she carried the dog to save its paws. And when the dog eventually died, she skinned it, stuffed it and continued to carry it along.

North of Whitehorse, Alling secured a boat and drifted down the Yukon River to Dawson City, where she spent the winter of 1928 working as a camp cook. She left again in spring, armed with a one-word answer to those who asked her destination: “Siberia.”

She had already walked thousands of kilometres, often covering 60 kilometres in a single day. By August, she’d arrived in Nome, Alaska. She was 200 kilometres from the Bering Strait, nearly to Russia. She set out for this last stretch pulling a cart, spurred forward by desire to get back home.

And then she vanished. Alling’s cart was discovered only 35 kilometres west of Nome. She was never heard from again. J. Irving Reed, a mining engineer in the town, was one of the last to see her alive. He wrote: “She took a chance, as many another traveller had done before her, and lost.”

The ghost ship

Abandoned to the polar mists, she sailed on—then disappeared

The S.S. Baychimo didn’t seek a place in the foggy mists of Arctic lore. She was a 1,332-tonne working vessel, a ship tasked with supplying Northern communities, and for many years she did her work diligently. Built in Sweden and sold to the Husdon’s Bay Company in 1921, she sailed to the many corners of the North, from Labrador to Siberia and most points in between, ferrying loads of kerosene, salted beef, pickled cabbage and Sapporo beer, and carrying missionaries, bureaucrats and “Hudson Bay boys.”

Then, in the summer of 1931, on a routine run past Alaska, she encountered ice like never before. After months of gruelling effort to push the Baychimo through to warmer waters, her crew was forced to abandon her near Wainwright, just west of Barrow. Less than two months later, in a furious early winter blizzard, the Baychimo disappeared. Her crew believed she’d sunk, her hull pierced by the ice that pressed in on all sides.

What they didn’t know was that just days later, the vessel – soon called the ghost ship of the Arctic – would sail clear of the fog long enough to make her first tantalizing reappearance. Little more than a week after she was lost in the storm, the Baychimo was spotted by a trapper and two Inupiat men. The sighting was brief. Soon, she drifted off again.

Two years later, the crew of a small supply ship found her stuck atop a pan of ice, drifting with the currents, a broken wooden ladder and rope still providing access to her decks. On those decks remained bags filled with mineral ore and caribou skins. The bridge was crammed with maps of the world’s seas; the dining room tables still bore menus for a six-course breakfast. They looted what they could and left when their own ship could hold no more without sinking. Inuit later returned and took for themselves the soap and sweet pickles they found on board. But before anyone could come to tow the Baychimo to port, she vanished again.

For the next decade the Baychimo would regularly rear her head, and hunters, trappers and salvagers would clamber aboard to unload liquor, lifeboats and anything else of value. When a rumour circulated that her holds stored a million dollars worth of cargo, treasure-hunters hired aircraft to find her. They failed.

Inupiat sealers sighted her in 1962 and then, perhaps, again in 1969. Nearly four decades had passed since she was first abandoned. Then, the sightings ceased. In his book Baychimo, Anthony Dalton concluded, “The twisted and flattened metal that was once her hull must now, in all probability, lie in the cold mud at the bottom of the Arctic Ocean.”

The cold mission

He set out to conquer the Siberian seas. They, instead, conquered him

Looking back, it should have been obvious that when Vladimir Aleksandrovich Rusanov set out for the Arctic in 1912, he was sailing into trouble. The young geologist had sparred with authorities from a young age, beginning at the University of Kiev, where he was expelled as a teen for taking part in “student disorders.” He spent his next few years in and out of jail. His fortunes seemed to improve when the Russian government asked him to stake a claim to the coal-rich islands of Svalbard, in the European High Arctic. It was to be a summer trip, but when Rusanov loaded his chosen vessel, the Gerkules, he stuffed it with food for two years, ammunition for 18 months and winter clothes for his entire crew. And he brought along his fiancée, a Frenchwoman he snuck on board on the strength of her education in medicine and geology.

He informed his bureaucratic masters with a brief telegram: “Have inspected all mining operations. ... Much ice. Am going east.”

The trip began well. The Gerkules – meaning “Hercules,” a name that brought ridicule given the vessel’s small size – quickly made land at Svalbard, where Rusanov inspected British and American mining operations, staked 28 claims for his homeland, and cheated death when he survived a fall into a glacial crevasse.

Emboldened by his success, he soon revealed to his crew his real intentions. He wanted to sail the Northeast Passage, a sea route he saw as vital to Russia’s economy and security. He informed his bureaucratic masters with a brief telegram: “Have inspected all mining operations. ... Much ice. Am going east.”

The waters he was about to enter were treacherous at the best of times, but it was now late August. He sent one last ominous telegram, naming the islands he would retreat to “if the ship is wrecked.” It ended: “Supplies for a year. All well. Rusanov.”

It was his last message to the outside world. Decades of searching, some of it sponsored by Soviet newspapers 60 years later, turned up traces on unnamed islands in the Kara Sea: shotgun shells, sheets of paper, a Kodak camera with rotted bellows, and French coat buttons. But the Gerkules, Rusanov and his fiancée vanished into the Arctic.

The lost world

On a cold coast, a people rose to glory and then were no more

In the early days of World War II, a small team of archaeologists announced a shocking discovery. On a remote Alaskan coast, at a place called Point Hope, they’d found what they called the most extraordinary Arctic treasure ever unearthed. Here, buried beneath the tundra, was evidence of a “lost Arctic city” of perhaps 5,000 people – larger than either Fairbanks or Juneau at the time.

The archaeologists discovered more than 600 houses, built alongside what appeared to be wide boulevards. And they found slim arrowheads, complete with barbs, suggesting the inhabitants were sophisticated warriors.

Equally intriguing were the fantastic ritualistic artifacts the culture had left behind. In graves they uncovered bodies buried with intricately-carved ivory death masks. Others had skulls inlaid with eyes of obsidian, ivory or jade. One of the graves held a body buried on top of a walrus. Another contained a person and a mummified dog. Some graves held mummified birds and other small animals, also with obsidian eyes.

The findings were so radically unlike anything ever before discovered in the North that it was clear whoever had made these – probably between 100 and 1,000 AD – bore little relation to the people we know as modern Inuit.

So who were they? And what became of them?

The Ipiutak, as the strange and fascinating culture would come to be known, became a source of tremendous inquiry. Further mysteries ensued: Soon after the discovery, a barge filled with artifacts sank off the Alaskan coast.

Archaeologists have since determined the population of Ipiutak likely numbered no more than 400. Yet such answers have given rise to far more questions that, even six decades after the find, remain unanswered: Where did they come from? What did they eat? Were they shamans? Were they warriors? What kind of societal structures did they use?

But perhaps most intriguing of all is the question that’s most difficult to answer: How did a people so rich in resources and artistry simply vanish from the face of the North?

The haunted isle

He wanted Northern gold, but what he got was a faraway grave

Many of the particulars about James Knight are unclear: his birth date, his appearance and, most confoundingly, the date and manner of his death.

This much is known: Knight was a haughty Englishman who, for four decades in the late 1600s and early 1700s, ruled the southern reaches of Hudson Bay with a dictator’s fist and a prospector’s lust for riches. Under the employ of the Hudson’s Bay Company he was, for a time, “Governor & Commander in Chief of all and every of Our Forts Factory’s Lands and Territory.”

But amid waging battles against French traders and even-more-vicious mosquitoes, Knight nurtured his real dream: discovering treasure. His colleagues nicknamed him “the goldfinder.” Everywhere he went, he demanded information from the local aboriginals: Had they seen “yellow mettle”?

He set sail in 1719 for Hudson Bay from a British port named Gravesend. It would prove a fittingly-named point of departure.

Nearing 80 years old, finally tired of governing a land he described as a “misserable barren place,” he convinced the HBC to let him pursue his gold-hued ambitions. Equipped with two ships – their holds packed with chests specially designed for the fortune he expected to mine – he set sail in 1719 for Hudson Bay from a British port named Gravesend. It would prove a fittingly-named point of departure.

Today, Knight’s ships, the Albany and the Discovery, lie at the bottom of the waters off Marble Island, a wedge of gleaming white rock not far from today’s Rankin Inlet, Nunavut. On the island are the remains of two structures Knight and his men built, presumably so they could overwinter.

What happened to Knight and his crew? Inuit would later tell explorers they watched the men starve, some expending their final strength on burying each other. Yet modern investigations reveal no graves on Marble Island. Was the Inuit account accurate? Some historians have concluded Knight was murdered by the Inuit. Others suggest an even spookier fate: Inuit have long considered Marble Island haunted, and even today, in deference to ancient legends, they crawl up its shores rather than walk.

Whatever happened to Knight on the shores of Marble Island, the truth about what writer Peter Unwin called “the greatest mystery in Arctic exploration” may never be known.

The headless men

They sought Nahanni's treasure—and paid for it with their lives

Half a century ago, when memories of the unlucky McLeod brothers remained fresh enough that their story was still recounted in newspapers and magazines, the Alaska Highway Handbook called their mysterious final resting place “The Valley of Vanishing Men.”

That valley is now known by a name that’s every bit as ominous. Deadman Valley in the Northwest Territories became a grave for Frank and Willie McLeod – goldseekers, sons of a Hudson’s Bay factor at Fort Liard, and keepers of a mystery that will likely never be solved.

The two brothers were raised, as author R.M. Patterson recounts in his book Dangerous River, “as Indians,” surrounded by the First Nations people of the southern Northwest Territories. At some point, those people told the brothers a story that tantalized them. They said there was gold to be found along the Flat River, a Nahanni River tributary less than 250 kilometres from Liard. The McLeods were determined to find it and get rich.

Charlie McLeod mounted a search and discovered an engraved wooden sled runner that read: “We have found a fine prospect.”

But it wouldn’t be easy. Between the brothers and their promised fortune lay a great fortress of jagged peaks. Seeking an easier way in, they took what must stand as one of the most bizarre trips in Northern history. In January 1904 they went to Edmonton, then Vancouver, then up the coast of Alaska to Wrangell Island, just north of modern-day Ketchikan. From here they trekked up frozen rivers to the Yukon, and finally over the continental divide to the upper Flat River.

There, they found First Nations whose gold-panning had yielded “some big stuff” – some of it worth what was then a considerable $3 per nugget. The brothers immediately set about searching for gold themselves, although that summer the largest nugget they found yielded only 50 cents, and they only found enough to fill a toothache-remedy bottle. Their attempt at real treasure would have to wait: With time running out for the season, they improvised a boat out of sluiceboxes and floated down the Flat and Nahanni to Fort Liard, where they began scheming their next foray.

Their chance came the following summer. Accompanied by a Scottish engineer – his name isn’t known – they set out. Their faces were never seen again. Three years later, their brother Charlie McLeod mounted a search and discovered an engraved wooden sled runner that read: “We have found a fine prospect.”

He also came upon their bodies. But, chillingly, their heads were gone. Nor did he find their gold. Rumours circulated about the Scotsman selling thousands in nuggets and dust in southern towns – but he, too, vanished. Did he murder the brothers for their gold? Were they killed by Nahanni Valley First Nations? Or did they, as the RCMP concluded, starve, their heads perhaps dispatched by wolves? The answer is as elusive as the McLeod brothers fabled treasure.