Side-hilling strains our knees and scrub birch grasps our ankles, but after four hours of struggle we leave behind the thickets that dominate Twelve Mile Valley and reach the green alpine meadows of Sheep Pass.

We are six days into a 12-day backpacking trip around Tombstone Territorial Park’s famed jagged spires. Few travel this deep into the park. Moose and grizzly and Dall’s sheep created the trails here. The valleys are thick with willow and alder, the alpine steep with shifting talus.

Here, atop Sheep Pass, under a stifling hot autumn sun, the Tombstone Mountains stretch before us. While I see this as an opportune time for a brief picnic to refuel for the eight kilometres of infuriating bushwhacking that still lie ahead, John, my partner, has other ideas.

Intense heat is John’s catnip. It is on these rare sweltering days that John is lured from reason and compelled to expose his nether regions to the full glory of the sun. I, however, do not think we have time for all of John to bask in this fine day. “We still have a lot of ground to cover today,” I remind him. But it’s a futile plea. Once the boots come off and the soles of his bare feet touch the cool, rough leaves of bearberry, he is past any point of reason.

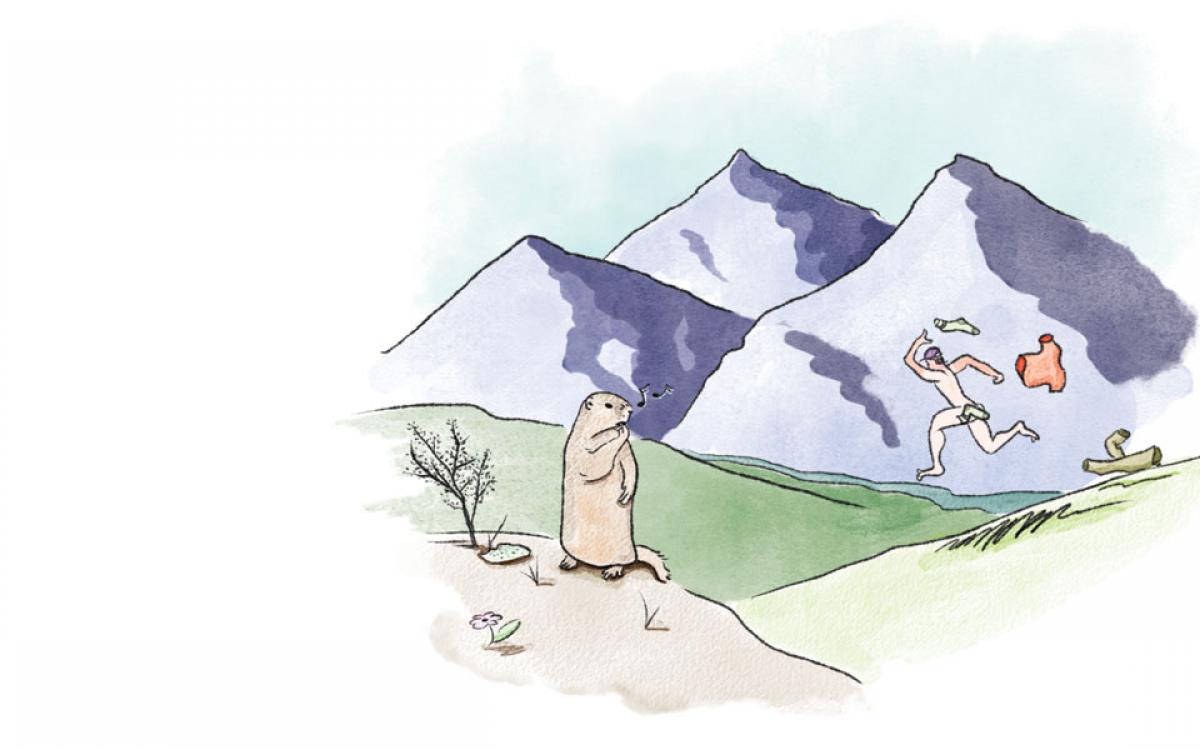

As John pulls off his t-shirt and unzips his pants, marmots on the hillside begin whistling. I settle against my pack, ignoring the shrieking rodents as John prances along the crest of the pass. My gaze shifts from blooming wildflowers to Yoke Mountain, then over to John, drunk on sunlight, skipping, his bits flailing in the breeze. I try to pick out the marmots from their rocky habitat, but their coats provide flawless camouflage. Instead, I spot a grizzly ambling down from Sheep Mountain. Towards us.

Suddenly, I can make sense of the marmot cries. They don’t care about me sitting here in the flowers or the naked guy frolicking about—they’re whistling at the adult male grizzly traversing their colony. Their concern has also become ours.

For a very brief moment, I admire the blond grizzly’s muscular shoulders before I leap up and look for John. He’s on a far hillside singing an East Coast shanty.

On one side of the pass is a giant griz. On the other, a skinny naked backpacker. I am in the middle, with John’s abandoned clothing and our bear spray.

“Bear!” I yell out to John. His singing halts. He stands motionless. His eyes follow my pointing finger.

He spots the grizzly and never have I seen him react so swiftly. He dashes across jagged rocks and tugs his clothes back on. His fingers fumble with the buttons on his shirt as I remove the safety clips from our bear sprays.

“Hello, Mister Bear,” I call out in a firm, but friendly voice. “Sorry to be in your way. We’ll be going now.” The grizzly continues his stroll towards us, but he still hasn’t seen us. We are standing downwind. Our scent is not reaching him and the rumbling of the creek between us drowns my lilting voice. His nose is to the ground, chasing the scent of marmot and Arctic ground squirrel.

In our two decades of backcountry experience, grizzlies are usually quick to run at the sight, sound or sniff of humans. Those who linger often stand on hind legs to decide what to do and determine what we are. I like to talk to these bears, pretending to be confident, like I was walking down a city’s dark alley with a stranger approaching.

Do not look vulnerable. Stand up tall. Act scrappy—perhaps even a little unpredictable. We must appear ready to fight and yet not appear threatening.

But this approach only works if the bear knows we are here. This one does not. And so we keep to our knoll, with the bear in our sights, and simply wait to see where it will go.

After several nervous minutes the winds shift and take our scent to the grizzly’s sensitive nose. His head rears up and in a heartbeat the grizzly turns away, his powerful hind legs pushing him up a steep bank. As the distance grows between us, the tension wanes. We return the safety clips to our bear sprays and feel comfortable enough to mock the grizzly’s behind, jiggling with generous stores of winter fat.

Meeting a grizzly can be the highlight of an adventure, despite the fears the encounter may elicit. Meeting a grizzly while naked reminds us of our vulnerability and how we are not the dominant species.

And John’s experience bares an important truth in wilderness travel: clothing may be optional but bear spray never is.