After four trips to the North—ranging from week-long visits to four-month stays—I have seen the aurora borealis just once, and that time barely counts.

There’s an expectation around aurora: the word evokes a sky painted in swirling lights, the land below bathed in impossible colours. My experience in seeing a handful of slim, faded green ribbons is not the aurora borealis people want to hear about. Southern friends and family can’t quite hide their disappointment that my experience doesn’t match the postcards, while Northerners wonder how I haven’t caught a more spectacular show by now—especially after living and working in Yellowknife, Aurora Capital of the World.

It’s not from a lack of trying. I’ve tracked weather and solar activity, but it never pans out. Friends, coworkers, and family have sounded the alarm while I visited, only for me to see their messages too late. I plan and I prep and I stare into a blank sky, and then the night I decide it’s safe to not look is the night the Northern Lights come out to dance.

At this point, it’s embarrassing. I’ve developed a talent for missing the most obvious sight in the North.

On my flight home from Yellowknife (my latest trip), I tried to mentally prepare myself to explain to people that I had once again failed to see the aurora. That would be everyone’s first question when I landed back in Ontario and I tried to resign myself to their inevitable disappointment. But, as I came closer to my final destination, I realized: I don’t think I care anymore. Yes, the Northern Lights are iconic—but after spending time up North, I’ve started to care more about the things people don’t talk about.

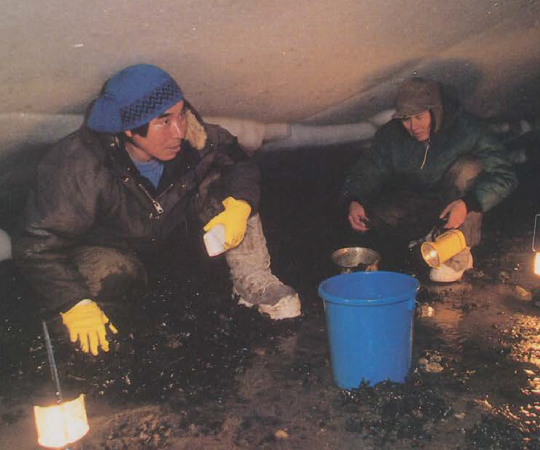

When I picture Yellowknife, I don’t see ribbons in the sky. I see the trees on my walk back from work—turned crystal-white from hoarfrost. I see the 9 am dawn, which I miss most of all (since as a chronic late-riser I hadn’t seen dawn for years), and the absolute black of the bush after sunset. My image of Yellowknife is now me sitting on the edge of Great Slave Lake on those last days of fall, hearing nothing but water lap on rock as I watch a pair of houseboaters set up on Mosher Island.

When it comes to the North, what I remember is if I step outside of the towns, the skies are so untouched by light pollution that I can see the shape of the Milky Way with my bare eyes. And that if I go at the right season, I can catch sunsets that last forever. The Arctic makes me think of beached icebergs in the summer, and how a wilted patch of Arctic Cotton in Iqaluit was still so beautiful it became my favourite flower.

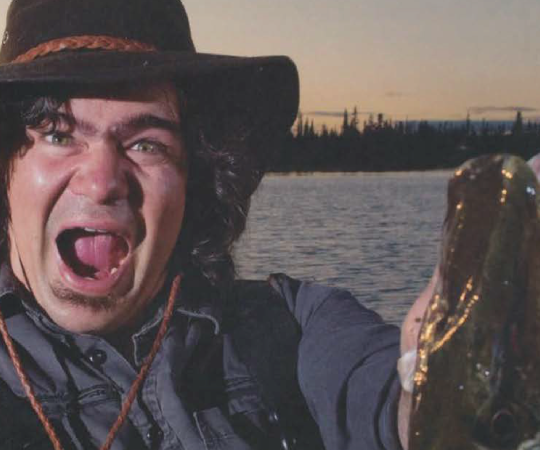

Whenever I head North, I stumble across more of these unexpected, everyday details that keep pulling me back. I even love my tiny aurora experience—as much as it disappoints others—because I caught it completely by accident. I was just driving into Fort Smith after dark with my grandparents, who live in the community. Ghostly green shimmers appeared overhead, stretching off in different directions, and a single strand followed us through all the bends in the road to my grandparents’ house. It was a brief moment that blew my mind, worked into the routine of a car ride.

So I’m going to stop chasing the postcard pictures of what the North is supposed to be. If I keep staring at blank skies, I’ll miss those secret wonders closer to the ground, or forget what makes the headline attractions so magnetic in the first place. And if that means my single green strand is all I get of the aurora, I’m satisfied. That strand plus all the marvels of the North is more than enough.