It was back in 2014 when a tall, white man with a Swiss accent first approached Harry Flaherty.

At the Northern Lights conference in Ottawa, where Northern businesspeople and politicians mingle with southern counterparts, this stranger said he had a few ideas, and could he have a few moments of Flaherty’s time. Flaherty, then interim president and CEO of the 100-percent Inuit-owned Nunasi Corporation, as well as president and CEO of Qikiqtaaluk Corporation, was wary. He’d heard this refrain before.

“My first impression was: What does he want from me? What does he want from us? I looked at him and said, ‘Well, who doesn’t have ideas to bring to Nunavut or to Indigenous people?’”

The man was Arnold Witzig, and he was polite but persistent. He’d been trying to reach Flaherty before the conference. Witzig would go on to tell Flaherty that he and his wife, Sima Sharifi, had recently founded the Arctic Inspiration Prize. The goal was to support small, community-led initiatives that don’t often fit within how southerners think about the North—meaning these projects get overlooked for crucial federal or territorial funding. Witzig was trying to get Northern organizations on board with the idea.

Flaherty, who was born in Grise Fiord and has lived in the Arctic all his life, recognized the talent, ingenuity, and ambition that existed all around him in the North. But at the time, he says, he felt there was a disconnect—Northerners needed a catalyst to encourage people to come together, to express themselves, and to bring their ideas to life. “When I had an opportunity to talk to Arnold, that’s exactly what he was trying to do,” Flaherty says. “His thoughts and ideas were right in line with what I believed in.”

He invited Witzig to Nunasi’s next board meeting to make a pitch. There, Nunasi committed to contributing $60,000 to the prize over the next three years—in addition to the $1 million he and Sharifi were donating annually.

Today, eight years later, Nunasi co-owns the Arctic Inspiration Prize, along with about 30 other corporations owned by Northern First Nations and Inuit. Its selection committees, comprised of Northerners and southerners, annually award $3 million to projects pitched by residents of the North—everything from local sea-ice monitoring in Nunatsiavut, to a land-based healing program in Yellowknife, to a welding studio in Cambridge Bay. The one thing each prize-winner has in common? They empower Northerners to tackle local problems their way and to improve the quality of life in their own communities.

This is the story of how it all happened—how a Swiss businessman-turned-philanthropist fell in love with the Canadian North; how he and his wife created the country’s largest annual prize; and how the prize has benefitted Northerners since it began a decade ago.

But this is not a story of southerners rushing in to save the day. Rather, they create the conditions necessary for uniquely Northern ideas to flourish—and then they walk away. It’s a story of unlikely allyship and southern dollars flowing north with no strings attached.

Witzig, for one, is a reluctant subject. He refused to be photographed for this story, and he intimated several times during the reporting process that he’d prefer the story be focused on Northerners now involved with the prize.

But without Witzig and Sharifi, there would be no Arctic Inspiration Prize. And many of the more than 40 ingenious, winning Northern-led projects that have used the prize money to get off the ground would not be where they are today.

As Wally Schumann, former NWT industry minister and incoming chair of the AIP Charitable Trust, puts it: “Ask yourself this one question, if you won Lotto 6/49… how many people would take it and give $50 million to put in trust to do what he’s doing? Nobody! Because nobody’s ever done it.”

Born in switzerland and growing up on the family farm, Witzig went on to study architecture. After heading a small firm, he built an engineering company that specialized in building sophisticated factories. According to his bio, “he understood that economic, environmental, architectural, technical and social needs had to be integrated in order to succeed, especially for complex industrial projects.” Witzig worked long days, with time for little else. Once his company expanded into Germany and became the market leader, he sold the business to his team in 1998, making every employee an owner.

Having achieved his business goals, Witzig decided to see what lay outside of Europe. His two children “challenged his view of the world from within the corporate walls of his business life,” according to his personal website.

Witzig narrowed down his starting point to San Diego or Vancouver—he wanted to climb mountains and improve his English, which was nearly non-existent. Ultimately, Vancouver won out.

He landed on July 1, 1999, and, that evening, watched a fireworks show in front of his hotel. How welcoming Canadians are, he thought. For a few months, he studied

English at the University of British Columbia (UBC), and that winter, headed to Fairbanks, curious about Alaskan cold and snow. Europeans know a lot about Alaska, he says. “We want to go there.” And then he met Sharifi.

Sima Sharifi had come to Canada in 1986 as a refugee from Iran, where she’d been an activist, protesting the government, organizing rallies, and graffiting walls. She was arrested several times, and once, imprisoned for two years. Ultimately, she was released with a suspended death penalty. “You are never safe,” she says. “They can always come and catch you for whatever reason and kill you.”

She was studying and working as a teaching assistant at Simon Fraser University and met Witzig on a dating website. Initially, she was put off by his profile, where he described himself as a businessman. “I have a problem with businessmen, ideologically speaking,” she says with a laugh. But she kept an open mind, and they began exchanging emails—Sharifi in Vancouver, Witzig still vacationing in Fairbanks.

“I saw immediately there are so many interesting things we had together—core values and so on,” Witzig says. “Even so, I was a capitalist and she was a left-wing activist, so there were also some things that were not in line, but the core values were there.”

He flew from Alaska to Vancouver to meet her, and invited her to come stay with him in Fairbanks. They returned to Vancouver later that winter, passing through the Yukon for the first time together. The beauty of the landscape struck them both; that highway drive planted the seed of their Northern love.

In 2004, Witzig and Sharifi were married. Over the next seven years, they worked with NGOs in Ethiopia, Bolivia, and Guatemala. The work was important to Sharifi. In Iran, her mother was Arab, her father Persian, and the family spoke Arabic. “Basically, we’re linguistically, ethnically a minority there and not liked by the dominating culture,” she says. “So I understand, I think, very well the working of colonialism—the working of dominant culture over the minority culture—and the long-term impact it has.”

The couple watched tensions flare in Bolivia under Evo Morales, the country’s first Indigenous president. Their thoughts turned to Canada, with its own devastating colonial history and wondered why they were working abroad when these issues existed in their own country. “We decided our backyard needs help too,” Sharifi says. “We should focus on our backyard first.”

When Karen Nutarak learned the early childhood education program she’d co-developed in Pond Inlet had won the $1-million Arctic Inspiration Prize, she called co-founder Tessa Lochhead and they both started crying.

Nutarak and Lochhead had opened Pirurvik Preschool—Inuktitut for “a place to grow”—in 2016. Later, they developed a program that taught kids a blend of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (traditional knowledge and cultural values) and the Montessori method.

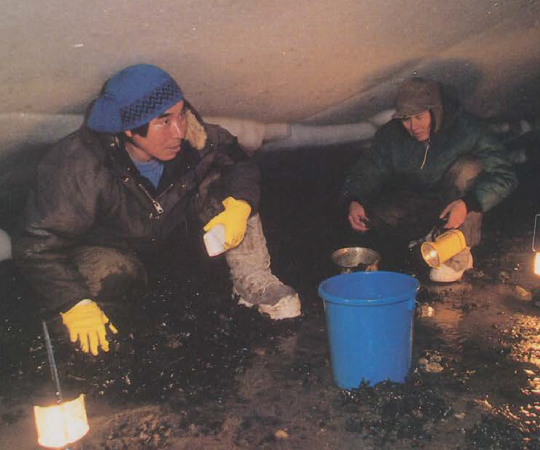

“A long time ago, before Inuit went to school, before the residential school and federal day school, children used to learn from their parents and there was no teacher,” says Nutarak. “Everything was observation, hands-on.”

The Pirurvik program relies on these traditional child-rearing practices, bringing ulus, scraping boards, sleds, and sealskins to children at preschool while also incorporating Montessori materials translated into Inuktitut. Parents have said their kids are more active at home and more eager to help out, Nutarak says.

Northerners know what will work up here and what won’t, Nutarak says. “We know our community. We know our people.” Southern programs and ideas aren’t always suitable for Northerners, she says, because life is so different down there.

“It was our dream to open a preschool that was based on our culture.” The prize has helped Pirurvik bring that dream—and their program—to four other communities in Nunavut.

Pirurvik’s win came seven years into the prize’s existence. Back in the fall of 2011, Witzig was finding inspiration in the Nobel Peace Prize. “We could see how a prize simply can have a much bigger impact in showcasing success, but also in generating support… You can build a whole network of supporters from North and south around this prize. When somebody wins the Nobel Prize, they are immediately visible.”

Witzig reached out to members of ArcticNet, a network of Arctic scientists and researchers, for guidance. “We had no idea with whom to talk. We didn’t know anybody in the North then,” Witzig says. “I was actually a bit afraid the idea of a prize would make us look pompous.”

ArcticNet took on the prize’s management. The inaugural selection committee was full of big Northern and southern names, including Susan Aglukark, Geraldine Van Bibber, Sheila Watt-Cloutier, Peter Mansbridge, and Michaëlle Jean. “That was the most important part, that the first laureates would be chosen by people that everybody would trust made the right decision,” says Witzig.

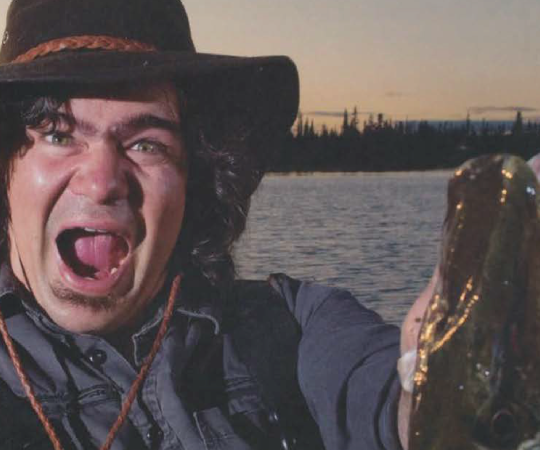

In 2012, with a $1-million donation from Witzig and Sharifi, the first four AIP winners were announced and they spanned the Canadian North. They included the Lutsel K’e Dene First Nation for its efforts to become stewards of Canada’s newest national park, Thaidene Nëné, on the East Arm of Great Slave Lake; the Nunavut Literacy Council for encouraging the use of literacy skills outside of the classroom; the book Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit - What Inuit have always known to be true, for preserving Inuit knowledge from elders for future generations; and the Arctic Food Network,

to develop food-sharing structures along snowmobile trails on Baffin Island.

“That was for us like a test if the whole idea might work or not,” says Witzig of the prize’s first two years. “Pretty soon, we saw that these winning laureates really had an impact… and that’s why we then said it seems to work.”

Around this time, Witzig was travelling often to the North, attending any public events he could—festivals, chamber of commerce meetings, mining conferences, anything—trying to spread the word about the prize and seek feedback from Northerners. “At the beginning, I was an absolute nobody and a southerner and nobody knew us, so it was not that easy.”

But once Nunasi came on board, in 2014, other Indigenous organizations did too. “He has been able to manage getting all these groups together in the North, all the way from Inuvialuit to Nunatsiavut, to Nunavut to north Quebec to Northwest Territories,” Flaherty says. “That’s a big accomplishment, what he’s been able to do.”

In 2016, the Rideau Hall Foundation took on the AIP’s operational costs, from flights and staff salaries to the televised awards ceremony. That meant any money contributed to the prize would now go entirely to winners.

Then, in 2018, Witzig and Sharifi made national headlines when they decided to donate their life savings—about $60 million—to the prize. “We were finally convinced that Northerners see the AIP as something they want,” says Witzig. “We came to the conclusion it’s the right thing to do and it’s the right time to do it.” (He did have to break the news to his two adult children that they wouldn’t receive an inheritance. They were understanding, he says.)

“It was a way for us to give back to our adopted country,” adds Sharifi. “I came to Canada and I was welcomed. I was given rights, like a Canadian who was born here. I didn’t have the right to live in the country where I was born… So for me, it was a golden opportunity to give back, and what better [way] than [to] strengthen the North? And as a result, make a stronger country.”

Witzig, 72, and Sharifi, 65, have lived full and fulfilling lives. He has climbed the Seven Summits—the highest mountain on each continent—and skiied to the North and South poles. Sharifi, meanwhile, has completed her PhD in translation studies.

“From a practical point of view, it doesn’t make sense to keep something you don’t need until you are dead, when you can invest it now in a way that it has an impact,” Witzig says.

Before Davida Wood accepted her position as the AIP’s first Yukon region manager in 2020, she asked around about Witzig. What was he like to work with? What did people think of the prize?

“I think, for Northerners across the country, there has been this aspect that things don’t come for free,” she says. There is often an unspoken expectation of some underlying return, in the form of access or ownership, when Indigenous Northerners share who they are, she adds.

A Teslin Tlingit Council citizen who runs a consulting business in Whitehorse, Wood wanted to make sure she wasn’t walking into anything like that. But everything she heard, and everything she saw in her conversations with Witzig, made her feel his intentions were pure and genuine. “I think that there is a very important space for this, whether we want to talk about it from a reconciliation lens or even the idea of bringing North and south together.”

Witzig says he’s scaling back his involvement in the prize, bringing on more Northern leadership. Wood is essentially its Yukon representative; her job involves promoting the award in the territory. In the NWT, the prize's board has hired former territorial health minister Glen Abernethy in a similar role, and he intends to bring on a manager for each of the Nunavut, Nunatsiavut, and Nunavik regions.

“The thing that I really appreciate is that he’s still intimately involved, but he’s handing over the reins more and more all the time to representatives from the Arctic, people who live here, who make decisions here,” says Abernethy.

The prize’s governance structure has developed over the years, too. A board of mostly Northern trustees manages the prize purse. Regional selection committees first narrow down applications, then a national committee makes the final choices. Today, the annual prize totals more than $3 million: the $1 million grand prize, as many as four prizes of up to $500,000 each, and as many as seven youth prizes of up to $100,000 each.

Southern companies with a stake in the North are also involved, giving financial contributions annually to the purse. This southern involvement is key—as Witzig puts it, the prize is “by the North, for the North, with unconditional support from the south.”

And he’s firm on that point. “Unconditional really means if there is southern support, they only should come on board if they are willing to let the Northerners do what they need to do, the way they want to do it,” he says.

Northerners come up with great ideas, says Abernethy, but these plans don’t always fit into a southerner’s worldview. Even in the North, he explains, Yellowknife politicians and bureaucrats try to push ideas that work in the capital into smaller communities. But federal and territorial governments hold the purse strings, so community-based ideas that work locally often get passed over for funding. The Arctic Inspiration Prize exists to recognize and support these projects that have untapped potential.

With the $60-million endowment wisely invested, plus annual donations from co-owners and partners, Witzig says the money should last forever.

Karen Aglukark and Rebecca Bisson have certainly seen the ripple effects from prize winners across the North. They’re team leaders with Northern Compass, a program that helps Northern youth pursue post-secondary education. After FOXY (Fostering Open eXpression among Youth) won $1 million in 2014 for leading youth-based sexual health and education conversations across the North, Aglukark and Bisson noticed, for the first time, some of their participants were openly gay and trans.

And then when Qaggiq—a program dedicated to strengthening Arctic performing arts—won $600,000 in 2016, they saw more and more young people were interested in careers in music.

“I think the Arctic Inspiration Prize just allows these smaller groups to change the culture of something in their communities,” says Aglukark, who is from Arviat. “Just to change the way we think about what we’re capable of in our communities.”

Northern Compass’s team members are prime examples. The project won $1 million in 2020, and they’re currently supporting 200 to 300 young people across the North with everything from tutoring to helping them prepare for college or university. “When you’re coming from a community that doesn’t have a lot of people who’ve gone on to post-secondary, you’ve maybe never been in a city, never been on a bus, never had a bank account,” says Bisson. “There’s so many additional hurdles.”

Winning provides teams with more than just money. It’s also external validation that they’re on the right track—recognition that others see their vision, too.

Derrick Hastings, the manager of the Farm in Dawson City, says it was reinvigorating to win $500,000 in 2019 to build a cold-climate greenhouse. “Sometimes you go through these lulls. You’re like, is this worth it?” he says. “Is all this work… gonna amount to really changing anything?”

Winning the prize told him it would. The farm, owned by the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation, plays an important role in the Dawson area when it comes to achieving food security and providing learning opportunities for the youth who work there.

“People believe in it,” Hastings says, noting the innovative greenhouse is now under construction. “You talk to elders, you talk to youth, and everybody sees the benefit in fresh vegetables in the winter and having a place to go and grow things. Everyone’s so excited.”

You couldn’t make the story up: a Swiss millionaire and an Iranian activist meet in Vancouver and agree to hand their fortune over to the Canadian North, a region they don’t live in. (Sharifi’s not a fan of the cold, and she’s terribly allergic to mosquitoes.)

Clearly, Witzig loves the North, but he’s happy to support residents from a distance instead of trampling them to do it. What he and Sharifi have done isn’t for their own fame or recognition. It boils down to respect—recognizing that the climate, culture, landscape, and traditions of the North are best known by Northerners and no one else.

Witzig recalls Canada Day 2019, when he and Sharifi visited former NWT premier Nellie Cournoyea in Tuktoyaktuk and celebrated his 20-year anniversary of coming to Canada. “It took me literally years to bring Nellie on board [with the prize], but now we are actually great friends and I have a huge respect for her,” Witzig says. She cooked up some caribou meat, and at 3 a.m., they went outside and watched children playing in the street in broad daylight.