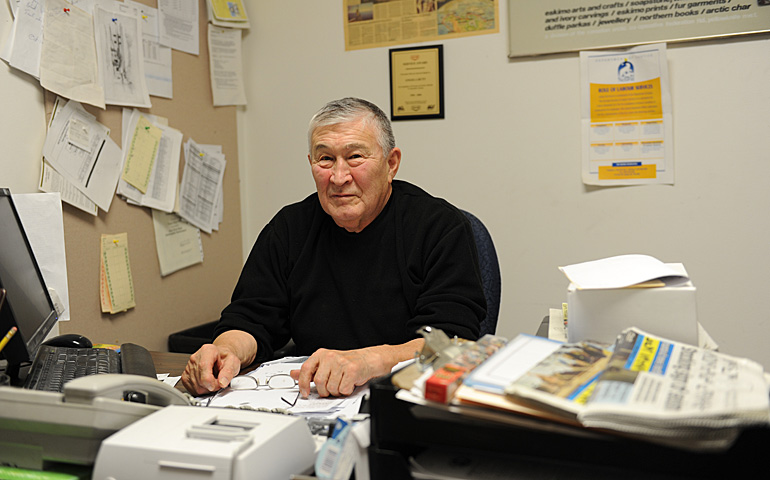

Bill Lyall, like most folks in Cambridge Bay, goes home from work to have lunch with family. Today, it’s turkey soup. The flu’s run through the hamlet of 1,600 over the holidays and it didn’t spare the Lyall house. Bill, 73, sits at the table, eating his soup and bannock. He’s nearly over his bout, but his sons and daughters, grandsons and granddaughters, pop in and out of the house, afflicted with various stages of the virus.

Lyall offers me a bowl while his great-grandson Frazer, 7, makes me a Keurig coffee. “Careful, my boy,” says Lyall, his eyes on Frazer, who hands me the steaming cup. It’s a little weak, but coffee is coffee. “Arctic char,” says Lyall, lifting his coffee mug. His eyes squint, accentuating the crow’s feet in the corners, and his face tightens a bit: I’ve learned this means he’s about to deliver a punchline. “That’s what I say when I cheers.”

I came down to his house on Natik Street to visit him away from his office at the local co-op store, but we never really get much talking done. He’s got lots on his mind. He looks out the window with concern: the loader operator needs to clear the snow properly down on the bay so he can set up for the annual New Year’s Eve fireworks show tomorrow. (The Lyalls pay for it from their own pockets, providing snacks and hot chocolate for Cambridge Bay’s little ones.) I meet Jessie, his wife, who offers me some bannock, and we start talking about how she got her start in teaching, back in 1986, and completed her Master’s degree in Iqaluit in 2009. “The best thing about it was my husband supported me all along,” she says. But her husband isn’t there. He’s off in a back room, helping a grandson find a part for his snow machine.

Part found, he sits back down at the table, but looks visibly agitated, glancing at the clock. It’s nearly 1 p.m. He has to be back for work. By the time the clock strikes one, he’s already out the door.

Bill Lyall doesn’t really take breaks. He’s a former MLA, a mechanic and chair or board member of countless local, regional and territorial organizations. In the summers, he runs a fishing lodge, B&J Flyfishing Adventures, with Jessie.

You’ll see him around town climbing up poles to fix cable boxes. Or running home to find a spare light bulb for a customer at the co-op grocery store. He works at the Ikaluktutiak Co-op seven days a week. “There’s nothing else to do,” he says, making that expression again.

If the busy days take their toll on him, you’d hardly know it by his work schedule. At 73, he admits he feels the aches and pains when he’s working out in the cold, or when he’s getting his lodge ready for guests in the spring. He’s no longer president of Arctic Co-operatives Limited, the organization that coordinates the federation of 31 community co-ops across Nunavut and NWT. It’s a position he’d held nearly continuously since 1981, though he was elected vice-president in May and is still on the board of directors, and insists he does just as much travel for the co-op as ever.

Somehow amid all this, he’s found time to release an autobiography. Well, sort of. Helping Ourselves by Helping Each Other: The Life Story of William Lyall devotes more ink to the co-operative movement in the Arctic than it does to William Lyall. And that’s fine with him. He wants the book to shine some light on the role co-ops have played in the North’s economic development. He hopes the book gets taught in schools.

“The world was changing and we were expected to go to school and get ready for it.”

Simply put, co-ops are businesses owned by their members—either customers or workers. These members benefit proportionally based on the volume of co-op services they consume or produce. Members also get to vote on co-op leadership and have a say in how profits should be used: for example, whether they be invested back into the co-op, into the community, or paid out to members as a dividend—or all of the above.

The co-op system immediately appealed to Lyall because its values mirrored Inuit customs. “The way it ran, it was so close to being the way our own people lived on the land, by helping each other, that everything is for everybody,” he says. “That way of life seemed to really fit together nicely with the economic development that was happening with the co-op system.” In the 1960s, co-ops made sense as a way to develop local economies in new permanent settlements, as money would stay in the community rather than leaving to southern or foreign ownership.

But this ownership-by-members concept was hard to explain in the early days, especially to elders who grew up on the land, not using money and instead selling pelts for tokens at trading posts. “That part is still really not recognized or really understood by a lot of people. Like, if it’s mine, how come I can’t take a loaf of bread home?” Lyall says. He would explain that selling the bread was the only way to pay for it getting to Cambridge Bay. “If everyone took a loaf of bread, we wouldn’t have this here.”

Time and circumstance conspired to make Lyall an ideal spokesperson for the co-ops. He was born at the right time, he says, “between the old time and the new time.”

Lyall spent the first eight years of his life learning hard work in Fort Ross, along Bellot Strait at the northern tip of the Boothia Peninsula, the most northern point on the North American landmass. He lived there with his extended family, and no more than 60 people in all. “It was very tough living up there at that time,” he says. His father, Ernie Lyall, helped build the local Hudson Bay Trading Post. (Ernie’s got an autobiography of his own—An Arctic Man—which documents Inuit families’ transitions into life in communities.)

Bill vaguely recalls planes flying overhead during World War II. “I could remember the Hudson Bay factor telling everybody, you’ve got to close your curtains and, you know, no lights shining out. Because of the war, the planes might see you and drop bombs on you,” he says. He’d watch the adults listen to the radio in English, but wouldn’t understand what was being said because back then he didn’t speak a word of the language. Mostly what he remembers, though, is all the hunting and fishing he got to do.

‘You Eskimos, you eat raw meat, your clothes stink’ and that type of stuff was instilled into you, you know.”

When supply ships couldn’t get into Fort Ross, the trading post was moved to Spence Bay (now Taloyoak). But there was no school there at the time. His father insisted that “to lead a good life, you need to have a job, and education was a must,” says Lyall. “But we didn’t know what education was in the beginning.” In 1950, Lyall traveled by Canso, a WWII aircraft, then by ship to Aklavik to attend residential school. “The world was changing and we were expected to go to school and get ready for it.”

It was there that he learned English. And lost his Inuktitut. “After four years, I completely put it away,” he says. “The thing was, it was drilled into you that you didn’t need it. It was not the way to live. ‘You Eskimos, you eat raw meat, your clothes stink’ and that type of stuff was instilled into you, you know.” Even to this day, he still hasn’t gotten his language back entirely.

Done school in Aklavik, Lyall moved to Yellowknife in 1958 to attend academic trades at the brand new Sir John Franklin High School, before heading farther south to Alberta to apprentice as an automotive mechanic. It was now 1968 and it’d been 19 years since he spent Christmas with his parents, so he flew back to Taloyoak. On his return trip, he stopped in Cambridge Bay. “I ran out of money and I’m still broke,” he jokes. He’s been in Cambridge Bay ever since.

Though he’s not exactly broke—or at least, it doesn’t appear that way—he certainly doesn’t live in a castle, like some other Northern leaders. Though governments have courted him over the years, Lyall’s chosen to spend his life with the co-op.

That’s not to say he didn’t give politics a shot. He won a seat on the settlement council, while he was pulling wrenches with the power corporation. And then, in 1975, he successfully ran for MLA, in the first fully-elected Legislative Assembly in the pre-division NWT.

But it was a frustrating experience. “As a young man at that time, I thought I could do something for my people,” he says. “It looked so easy to do.” But once he got to Yellowknife, he quickly found out that five-, 10-, 15- and 20-year spending plans already existed. “You were just there as a figurehead, really.” When he’d return to Cambridge Bay, he had nothing to do, so he started to get involved with the fishery.

The waterways surrounding Cambridge Bay are blessed with a bounty of Arctic char. The commercial fishery—a government “make-work project” as Lyall calls it—was launched back in 1961 and early on operated as a quasi-co-operative, with fishermen bringing in their catch for processing at the plant. Back then, char would arrive around the clock—sometimes at 4 a.m.—and workers would come in to gut and treat the fish. “When we operated it, it was 24/7,” says Lyall. (The co-op purchased the fishery from the government in 1977, but later sold it to the Nunavut Development Corporation, retaining a 49-per cent stake.)

Lyall’s been president of the local co-op since 1978 and what started out as a fishery has become much, much more: two hotels, a gas bar, a taxi service, a television cable provider, a restaurant and a retail and grocery store. It employs 27 people in town and, according to his book, pays out $140,000 in wages each month. (Across the North, co-ops are the largest private employer of aboriginal people, says Lyall.)

It hasn’t been all successes, though. The co-op started a bakery, but to make money, it had to make more bread than Cambridge Bay could handle. So it eventually shut its doors. As did a sewing centre. Other ideas haven’t gotten off the ground. Lyall wants to open a local credit union, and would like to see more collaboration between co-ops and regional Inuit birthright associations.

Branching out is the only way to do business successfully in the North, says Lyall. “The store couldn’t work by itself,” he says, “so we started getting little contracts here and there, doing the mail run from the airport to town or doing a little bit of government work.” He mentions another company in town that runs Green Row Executive Suites. “They’ve got a garage now. They’ve got a construction outfit,” he says. “But Green Row, by itself, I don’t think it could work either. You have to have something else to complement it to make enough money to make it work.”

“This summer, we would have had zero unemployment here. There was enough work here in town that we would have had that. But modern day people want to sleep till 9 a.m., go to work about 1 p.m. and then finish about 4 p.m. It’s not the same as it used to be.”

How did an automotive mechanic become a business leader? Lyall says he picked up his acumen “from grace and from God.” I’m not sure if the latter is a clever reference to his mentor, Father André Goussaert, an Arctic co-op pioneer and organizer in the late 1950s, whom Lyall credits for teaching him the ins and outs of business and then trusting him to run with it. (Lyall is Cambridge Bay Co-op Member #2. Goussaert is #1.)

Goussaert, now living in Winnipeg, says Lyall has always practiced what he preached. “He came right out to tell people, 'If you don’t support it, it won’t work,'” he says. Lyall tirelessly travelled to small communities to explain how co-ops worked. And he chaired annual meetings, where he wouldn’t mince words. If a member was bellyaching about something the co-op was or wasn’t doing, Goussaert says Lyall would ask that person, “How much business have you done with the co-op? Some people were really ashamed because they hadn’t done any,” he says. “So what right did they have to complain?” If another co-op wasn’t doing a good job of managing its affairs, Lyall would also go in and let them know.

Setting an example is important to Lyall. His work ethic comes from his parents, who cast a long shadow. Even in Alberta, 1,800 miles from home, when someone offered Lyall a drink or a smoke, he’d look over his shoulder, expecting to see his mother or father. (The work ethic was transmitted to the rest of Lyall’s siblings, a dynasty of politicians, businesspeople and civil servants across Nunavut.)

That’s why it’s hard for him to see people squander opportunities. “This summer, we would have had zero unemployment here. There was enough work here in town that we would have had that,” he says. “But modern day people want to sleep till 9 a.m., go to work about 1 p.m. and then finish about 4 p.m. It’s not the same as it used to be.”

Staffing is a challenge, which is aggravated by the competition with government. Many of the best and brightest, who are provided with skills and training by the co-op, are lured away by the bigger paycheques. “Here, we have a hard time keeping people employed,” he says. “If we didn’t have five people that really committed to do the work here, it would be a hard go.”

In recent years, Lyall’s hard work has started to get noticed. He was awarded the Order of Canada in 2003, which Jessie found out just as the family was taking a trip to Sweden, at the invitation of a former employee who’d made a film about his time in Cambridge Bay. On their cross-Canada flight, Jessie conspired with a flight attendant. “I wrote a note to say that Bill was getting an award,” she says. She asked her to announce it over the PA. When she did, everyone in the plane clapped. “Bill looked at me and asked, ‘why did you do that?’ I said, ‘Because I’m proud of you.’”

On the flight across the Atlantic Ocean, Jessie did it again. “He told me to stop,” she says, laughing.

In the summers, Lyall does get to relax, though he doesn’t really slow down. He enjoys going out on the land to hunt seal and make dry meat. The lodge he and Jessie started was supposed to be a nice retirement gig. But in the last few years, it’s just become more work. Bill and Jessie go out to Wellington Bay by boat for a few days in July to fill up the water tanks, do some cleaning and get the lodge ready for guests who start arriving in August—when the real work starts.

Though the days are long, and the tasks at times can seem endless, I’m sure deep down, that suits Bill Lyall just fine.