On the frozen Arctic Ocean near Tuktoyaktuk, with the ice-cored Ibyuk Pingo not far off in the distance, lies a zigzagging line of red broadcloth. Spanning more than 1,000 feet in length, the fabric is anchored in place by rocks dropped through 111 ice-fishing holes. From a bird’s-eye view, it resembles thread sewn into the snow, the undulating pattern not unlike the one adorning traditional parkas in the Beaufort Delta.

This is Stitching My Landscape—Inuvialuk artist Maureen Gruben’s first large-scale installation. She created it five years ago as part of LandMarks2017, a nationwide project that commissioned artists to produce works that explored their connections to the land.

“The piece stemmed from a memory of my brother pulling the guts out of a seal when we were [fishing] at Husky Lakes,” Gruben says. “He stretched [them] out, so it was like a long red line.”

This inspiration is emblematic of Gruben’s artistry. Weaving together her personal experiences and Inuvialuit culture, her pieces create an intimacy that is deeply moving and wholly engaging.

Since graduating with a BFA from the University of Victoria in 2012, Gruben has been regularly exhibited in galleries around the world, from New York to Norway. She was long listed for both the international Aesthetica Art Prize in 2019 and national Sobey Art Award in 2021. In less than a decade, she has become one of the North’s foremost installation artists.

But ask how she discovered her artistic talent, and she’s quick to tell you that’s not exactly how she sees it.

“I don’t think I discovered it,” Gruben says. Rather, it was simply a fact of survival growing up in Tuktoyaktuk. Her mother sewed everything from wedding dresses to airplane covers; her father carved fox pelt stretchers and mended fishing nets. “It’s like art is life and life is art,” she muses. “It’s not really separated.”

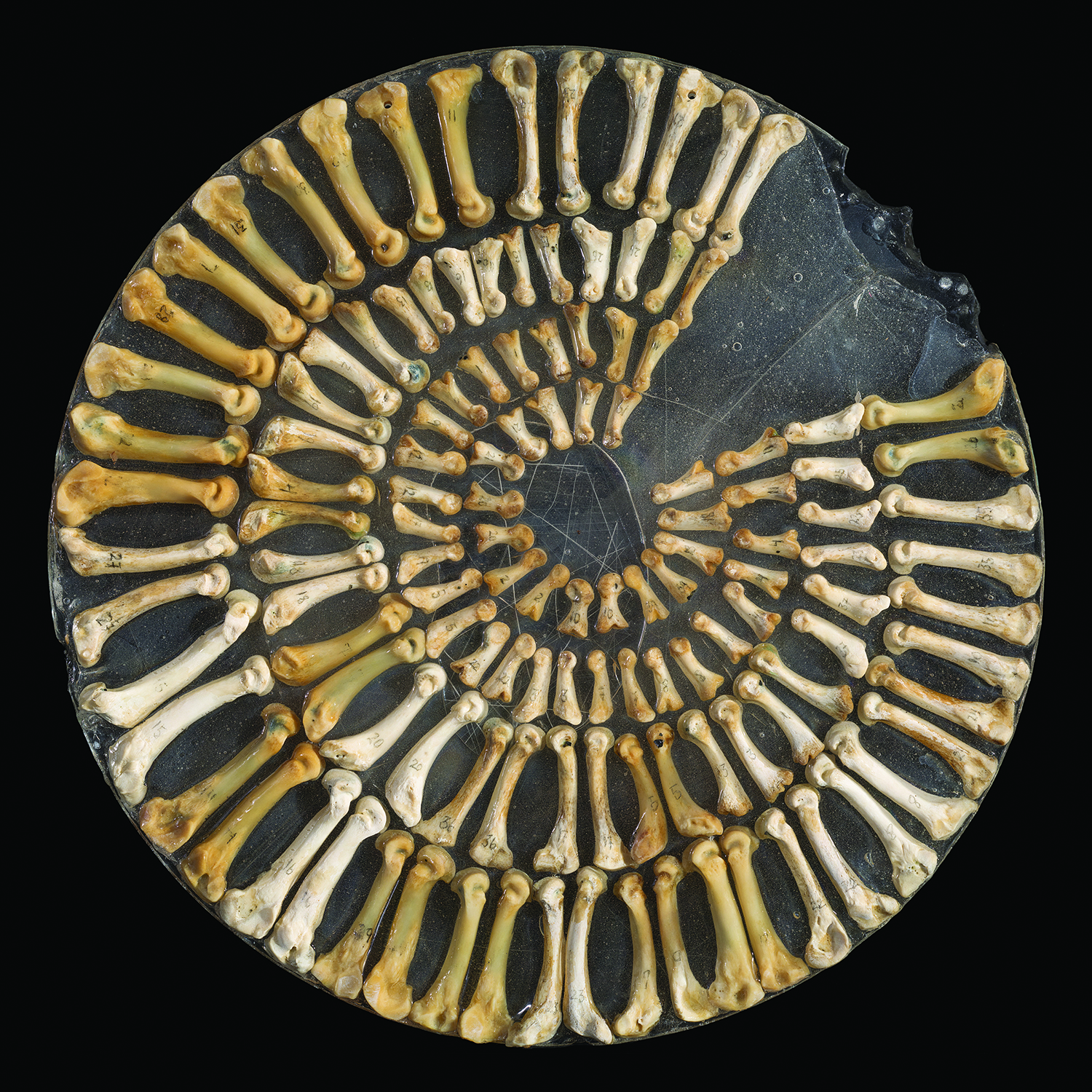

This sensibility propels her contemporary practice. Blending raw and synthetic materials in almost every piece, she creates a striking clash of natural and artificial worlds. Bones from polar bear paws are encased in resin. Elastic bands, earphones, and condoms are stitched into dried beluga intestines. Strips of moose hide, reflective tape, zip-ties, and bubble wrap are used to replicate some of her own mother’s sewing patterns.

Gruben uses these materials because they are readily available in Tuk and create compelling aesthetics. Yet these disposable items also offer a powerful visual commentary on how the modern consumer lifestyle has altered Arctic communities and created problems with excess waste. Each piece makes a subtle, yet undeniable, political statement.

This politicism is an element that’s become increasingly central to Gruben’s work. The Arctic is warming three times faster than the rest of the world—for climate change, it’s what the canary is to the coal mine. By virtue of living there, anything Gruben does is sure to evoke ideas of this seismic environmental shift.

Take Stitching My Landscape. Primarily derived from a memory in its creation, the final product also speaks to the disappearance of sea ice. While Gruben isn’t always one to discuss the meaning behind her art, preferring to let the piece do the talking, lately she’s come to relish the opportunity this moment in time has presented her and chooses to display her work on the ice itself more often.

“I’m looking at the ice as my gallery,” she says. “Putting installations out on the Arctic Ocean just has such a huge impact, even though there’s no one around, because it’s just a big white canvas.”

This sentiment is perhaps most poignant in her latest piece, completed this spring. Gruben recycled the red broadcloth from Stitching My Landscape (collected in a canoe after the ice melted in 2017) to create two 28-by-56-foot panels. She placed them at the same spot on the ice, near Ibyuk, in the shape of a cross, mimicking the Canadian Red Cross logo. It stayed there for two months, bringing attention to Tuktoyaktuk’s rapidly eroding coastline—a climate emergency.

Out there on the ice, with the arresting red contrasted against the white, the urgency in Gruben’s message is hard to miss. That’s the power of incorporating the landscape into her work. The artist gives the land a voice, hoping to inspire people to help protect it.

In July, Gruben was preparing to welcome interdisciplinary artists Scott Benesiinaabandan and Rebecca Belmore to Tuk for a 10-day residency in a bed and breakfast she operates. She wanted the two Indigenous artists to “experience the Arctic, the Inuvialuit, the waters, the land, and just have that in their consciousness” as inspiration. She hopes to offer a new residency every year.

“There’s just so much potential,” Gruben says. “Art is activation. It can be a catalyst for something that you’re very passionate about. And for me, that’s the environment and land in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region.”